This resilience toolkit teaches a step-by-step plan for resilience team building and neighborhood emergency preparedness.…

Santa Barbara Disaster Timeline

A Santa Barbara Timeline

A Santa Barbara Timeline

A Santa Barbara Timeline

A Santa Barbara Timeline

A Santa Barbara Timeline

Natural Disasters: A Santa Barbara Timeline

Saber es poder.

Knowledge is power.

This timeline of natural disasters in and around Santa Barbara County dates back more than 100 years to cover wildfires, floods, debris flows, winter storms, and two major earthquakes. As an educational tool, it is recorded history of common threats across our region. As we prepare for the future, we can learn from the lessons of the past. The information and images contained in this timeline can help us gain a greater perspective on the hazards we face here in Santa Barbara County. Without this knowledge, it’s impossible to properly prepare for the next natural disaster.

While this timeline covers significant recorded disasters, there are likely other events not included that you may have experienced personally or know about. Please do not hesitate to contact us with more information. We view this timeline as an evolving record and a good place to start a discussion about the history of natural disasters in our area. Where this conversation goes is up to all of us.

This tool is simple to use. Simply scroll along the timeline top to bottom. To jump to a specific date, scroll and click on the timeline bar on the right side of the page. Click on images to expand. Click outside an expanded image or tap “esc” to return to timeline.

This project was principally researched and written by Bucket Brigade intern James Kendrick, and designed by webmaster Andrew Hill. In particular, we would like to thank the Montecito Association History Committee for help and access to its archive, where we found many of the historic photos that appear in this timeline.

Santa Barbara Disaster Timeline

A major earthquake struck on December 21, 1812, causing severe damage to the Santa Barbara Mission buildings and the Presidio compound. The same earthquake also destroyed Mission La Purisima, near what is now the city of Lompoc.

The years 1906 through 1914 were especially stormy along the South Coast of Santa Barbara County, with five notable floods.

The first noted event occurred in March 1906 when heavy rains triggered a series of slides and washouts severe enough to shut down railways and damage most of the wagon roads throughout upper Montecito.

In 1907, another significant storm brought upward of five inches of rain to the foothills. Railways were once again blocked, and the swollen Montecito Creek jumped its banks and carved two ditches down the center of Olive Mill Road. As it approached the sea, the rushing water took another alternate path, flowing east towards the Miramar, flooding the hotel’s sunken gardens and forcing the relocation of many guests.

In January of 1909, another severe storm crashed into the Santa Barbara front country. Cabrillo Boulevard was completely flooded, and major landslides caused severe damage along Eucalyptus Hill. In 1911, storms caused more flooding and slides.

On September 17, 1913, 108-degree daytime heat paired with dry weather created ideal conditions for wildfire, fueling a small grass fire in Sycamore Canyon to grow quickly out of control. While the intense heat of the day made firefighting difficult, the Forest Service managed to quickly contain the blaze with the help of a handful of local volunteers. Unfortunately, the fire did claim the life of Dr. Charles Anderson as he battled the fire at his Mountain Drive home. Firefighters were able to gain the upperhand on the blaze by the end of the day.

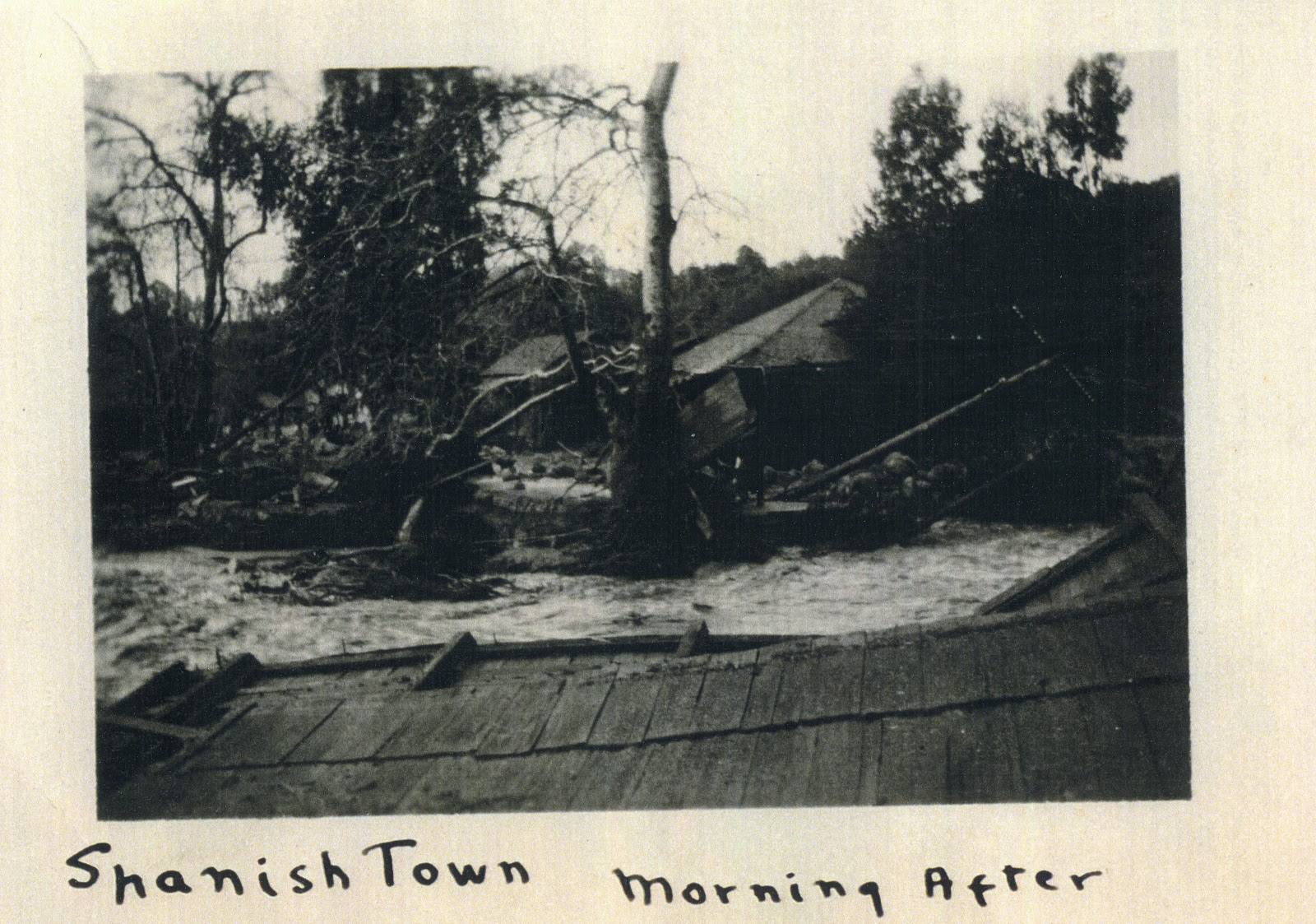

In the late afternoon of January 23, 1914, a storm cell hit the foothills of Montecito and Mission Canyon, dropping four inches of rain in two hours. To make things worse, the downpour came after three days of steady rain that had left the watersheds saturated. When the deluge hit, walls of water, mud, and debris came roaring down the canyons and creeks, washing out nearly every bridge in the south county. Below Mission Canyon, boulders and trees tumbled down San Marcos and Modoc roads and spilled into La Cumbre Jr. High. Further south, flows took out bridges along De La Guerra, Haley, and Ortega streets. In Montecito, 12 houses near Montecito Creek were washed away when the floodwaters overflowed from the creek channel and rushed down Hot Springs and Olive Mill roads. The storm left extensive damage to roadways and bridges, leaving the streets full of mud, boulders, and tree trunks.

Three deaths were recorded in the Santa Barbara area. One teenage boy was killed near La Cumbre Jr. High; his body was recovered from a ditch on Chino Street.

The other two victims were Mr. and Mrs. Jones. Mr. Jones was the president of the Santa Barbara Chamber of Commerce, and the two had been dining at the Montecito Country Club (then located at the current site of the Music Academy of the West) when the flooding began.

With phone lines out, the two attempted to make the journey back to their children, who were at home, located on the north side of East Valley Road between San Ysidro Creek and Park Lane. Unable to cross flooded Olive Mill Road, the couple abandoned their car and walked along the highway to the Miramar Hotel. Ignoring the owner’s pleas to spend the night, the couple took a lantern and attempted to walk home along San Ysidro Road. Unfortunately, the couple never made it and likely drowned while trying to cross Oak Creek. Their bodies were discovered the next day in a field near Montecito Union School. Fortunately for their children, the babysitter had noticed the rising waters of San Ysidro Creek and took the children to a neighbor’s house, located on higher ground.

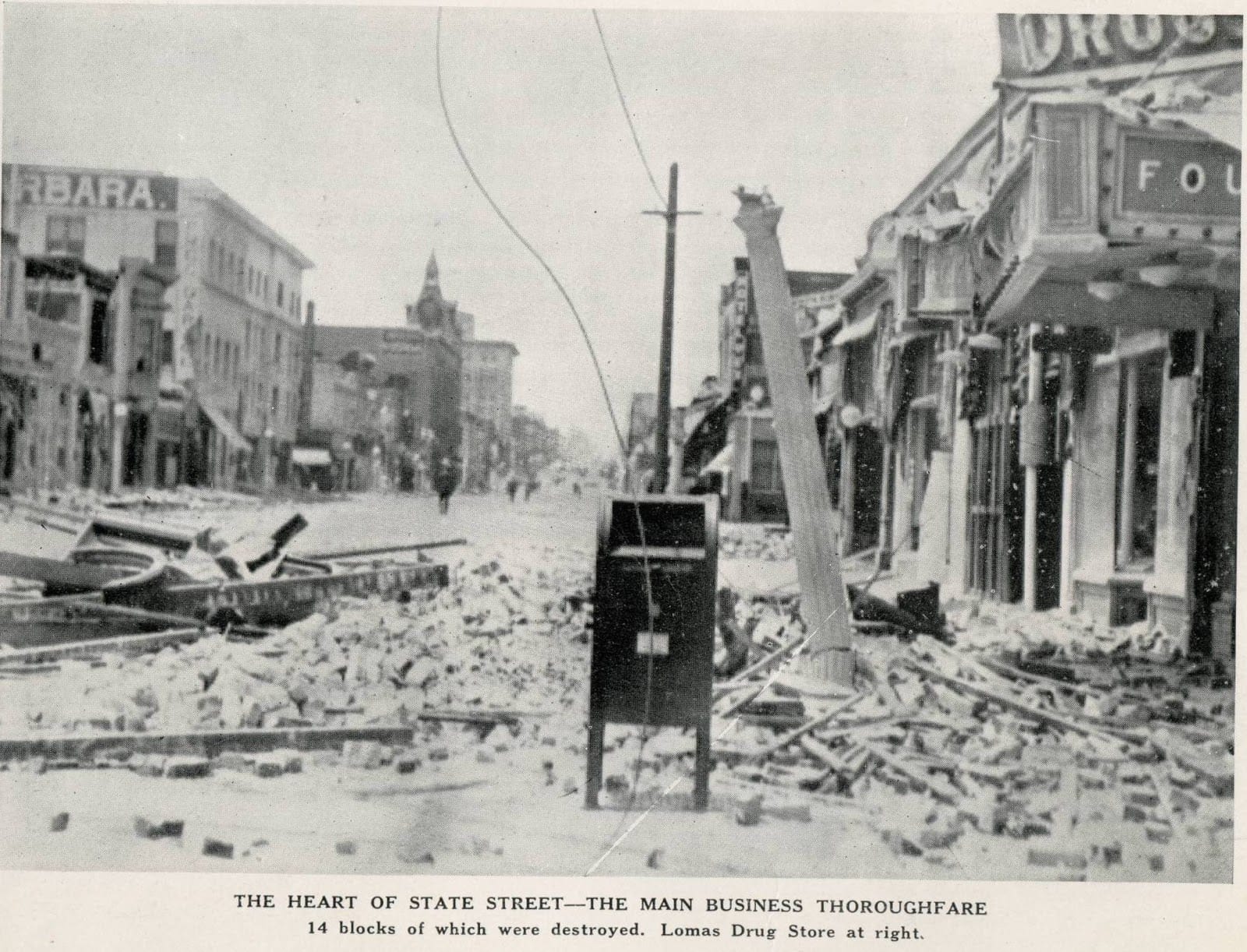

At 6:24 a.m. on June 29, an earthquake estimated as strong as 6.8 hit Santa Barbara, destroying 85 percent of the town’s commercial buildings in 18 seconds. The quake also caused liquefaction in the foothills underneath the Sheffield Dam, causing it to fail, releasing a 45-million-gallon torrent. This floodwave rushed seaward between Voluntario and Alisos streets, carrying trees, boulders, and urban debris. Fortunately, further damage was avoided when the local utility company shut off gas lines to prevent the eruption of major fires. Most damage occurred in the downtown area, with much of lower State Street being reduced to rubble.

Many Santa Barbara residents spent that summer sleeping outside, as aftershocks periodically rolled through, threatening unstable buildings. The quake caused $8 million in damages and claimed 13 lives, the last of which occurred exactly one year later, on June 29, 1926, when an aftershock caused a damaged chimney to collapse on a little boy.

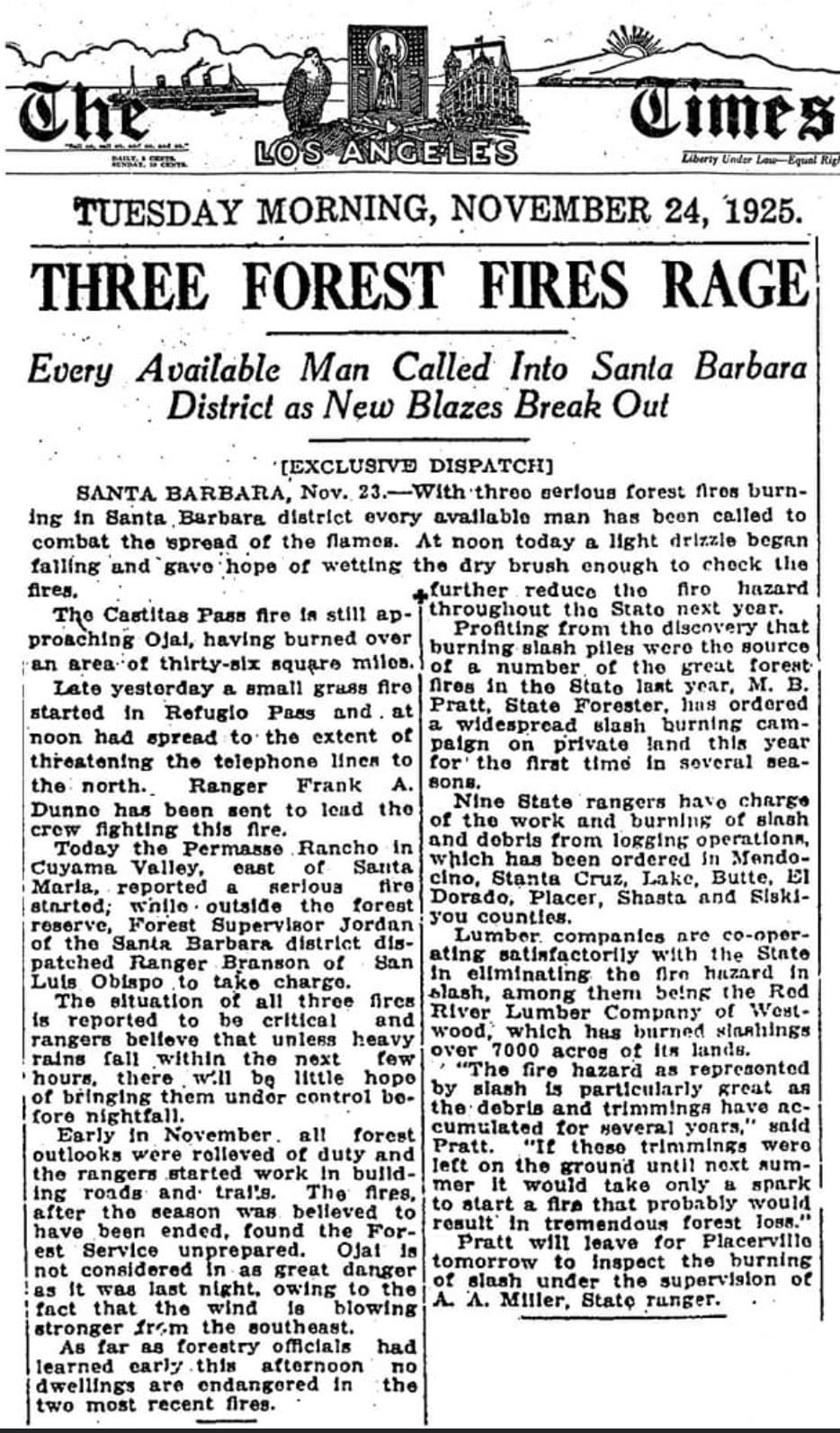

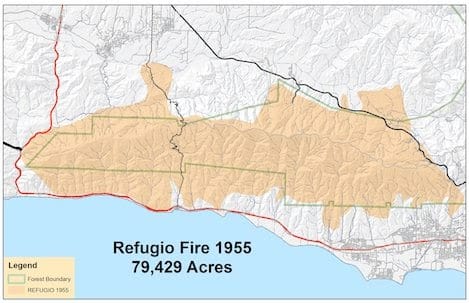

The Refugio Fire of September 1955 was one of the first large-scale wildfires to strike Santa Barbara County in the age of modern fire management. After the establishment of the U.S. Forest Service in 1905, strategy focused on the suppression fires, both natural and human-caused. Decades of rapid and effective response to even remote and naturally occurring fires allowed for a massive buildup of dry fuel through the entire San Ynez range.

At around 1 a.m. on September 6, a structure fire on La Chirpa Ranch (now named La Scherpa) triggered by an electrical malfunction, providing the spark that would trigger a massive 80,000-acre fire across the coastal range.

As ranch hands attempted to extinguish the burning structure, the situation rapidly grew out of control and a call was placed to the Santa Barbara County Fire Department. Realizing the fire was outside their jurisdiction, county firefighters contacted Forest Service personnel, who quickly mobilized to assess the threat. All hope of an easy containment was lost as winds caused the fire to grow rapidly in all directions. Initially, the Forest Service divided its resources to fight along the west, south, and east edges of the fire but this quickly overwhelmed their resources. After a hard-fought rescue of the Circle Bar B Guest Ranch, all efforts to save Goleta became a priority.

Firefighters utilized bulldozers and hand crews to create fuel breaks in the hills above Goleta as ridgeline fire began sending fingers down the canyons. However, as harsh winds persisted, these fire lines proved ineffective and were continuously overrun. Realizing that greater resources were needed, additional units were called in from across the state command units reorganized at the San Marcos Trout Club.

Firefighters managed to take advantage of extra hands as well as a pause in the wind to gain the upperhand on the fire’s western flank on September 8. As the fire’s westward threat was all but over, the eastern and northern flanks continue to burn into the backcountry uncontrolled before eventually running out of fuel and dying out on September 15. The fire’s sheer size and ferocity caused a fundamental shift in the way firefighters think about fire management in a chaparral environment. New strategies, such as controlled burning, fuel removal, and rapid/effective communication between authorities would become more relevant factors in managing forests in the years to come.

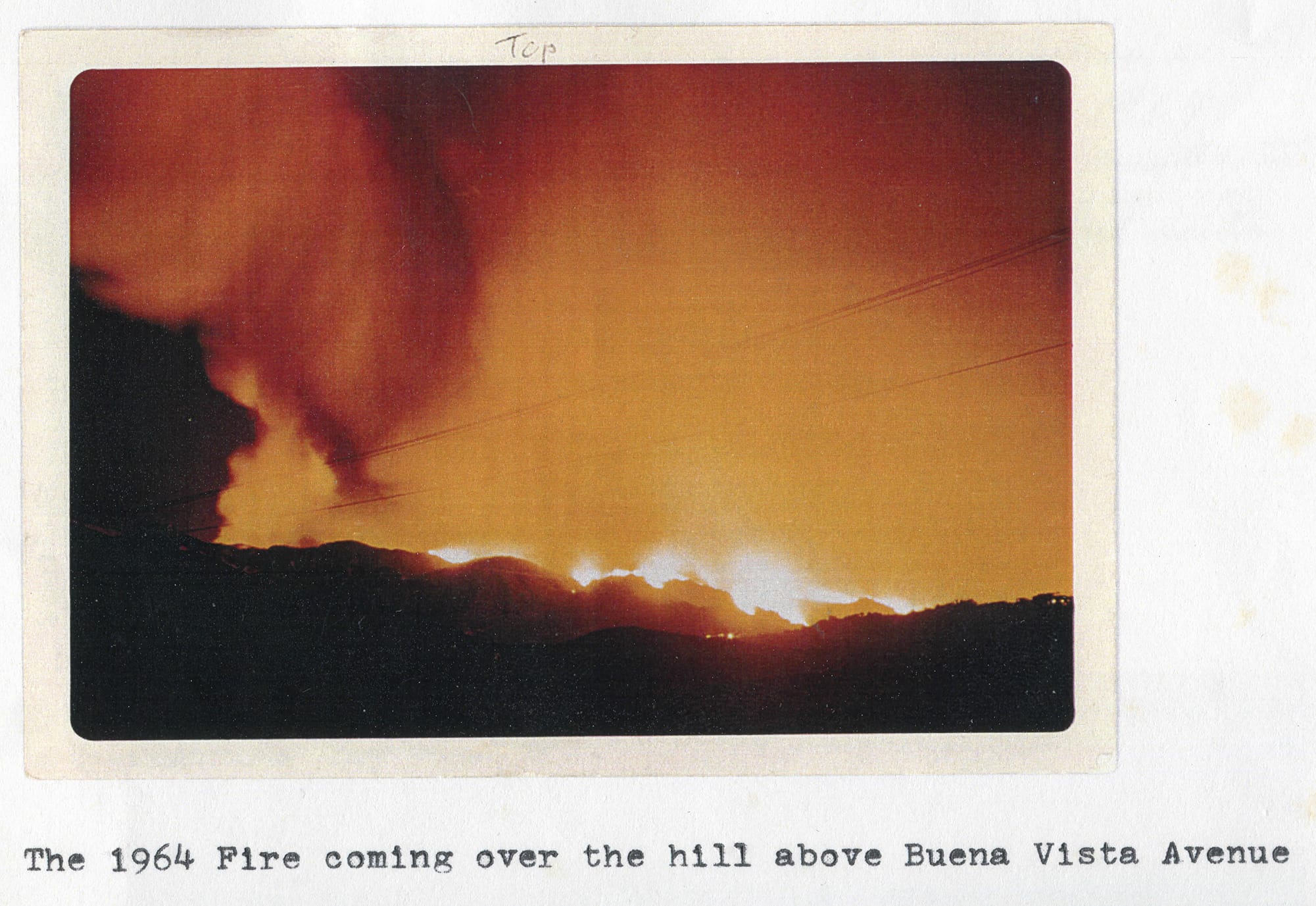

The Coyote Fire began on September 22, off Coyote Road, east of Sycamore Canyon, and burned for 10 days before being declared under control. The wildfire’s maximum perimeter was 160 miles and a total of 67,000 acres were burned, 21,000 of which was private land. There was one reported death and 18 injuries, as well as 85 burned homes. Roughly 30,000 acres of the burned area were in the south-slope mountain drainages at risk for subsequent debris flows.

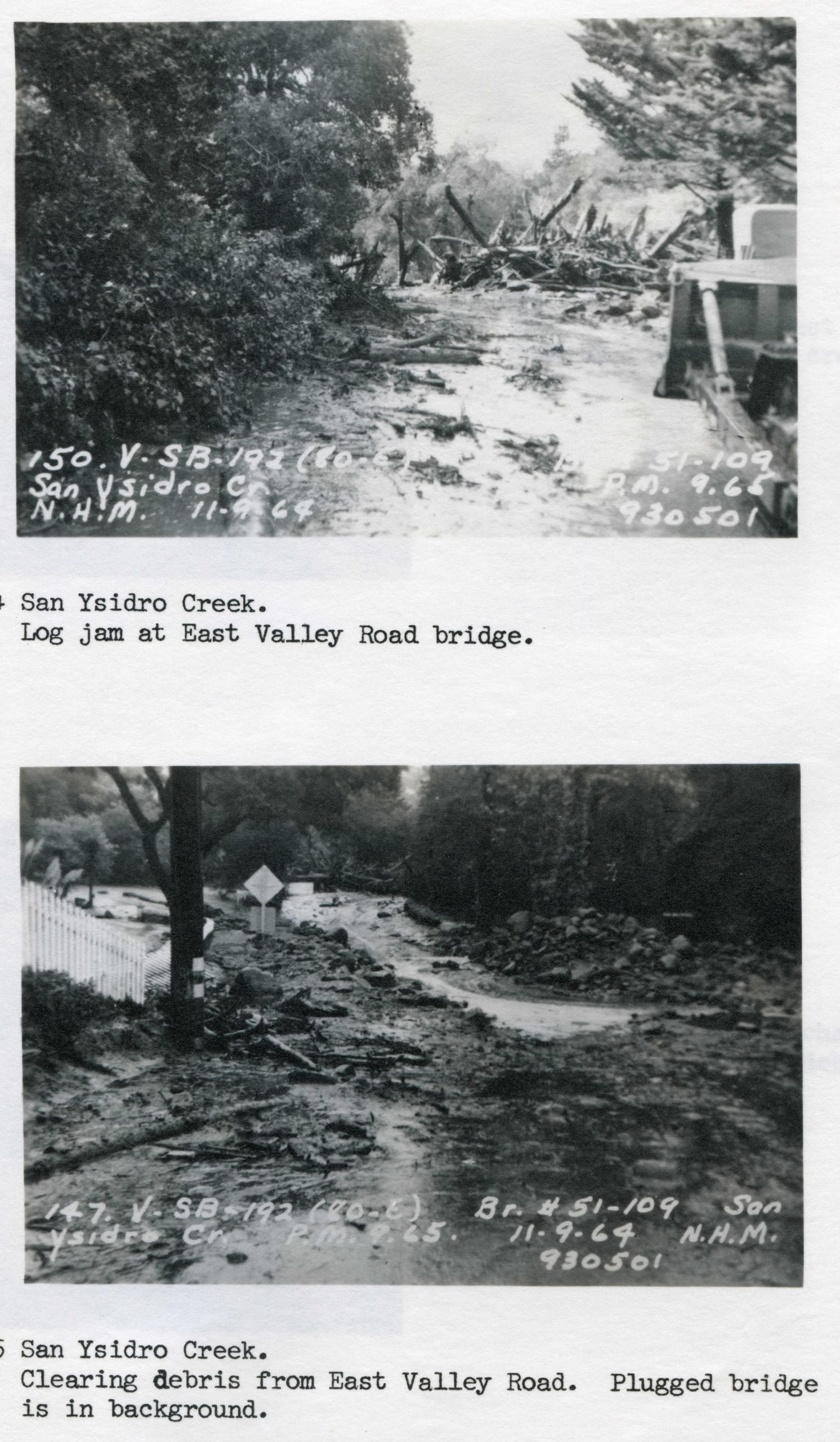

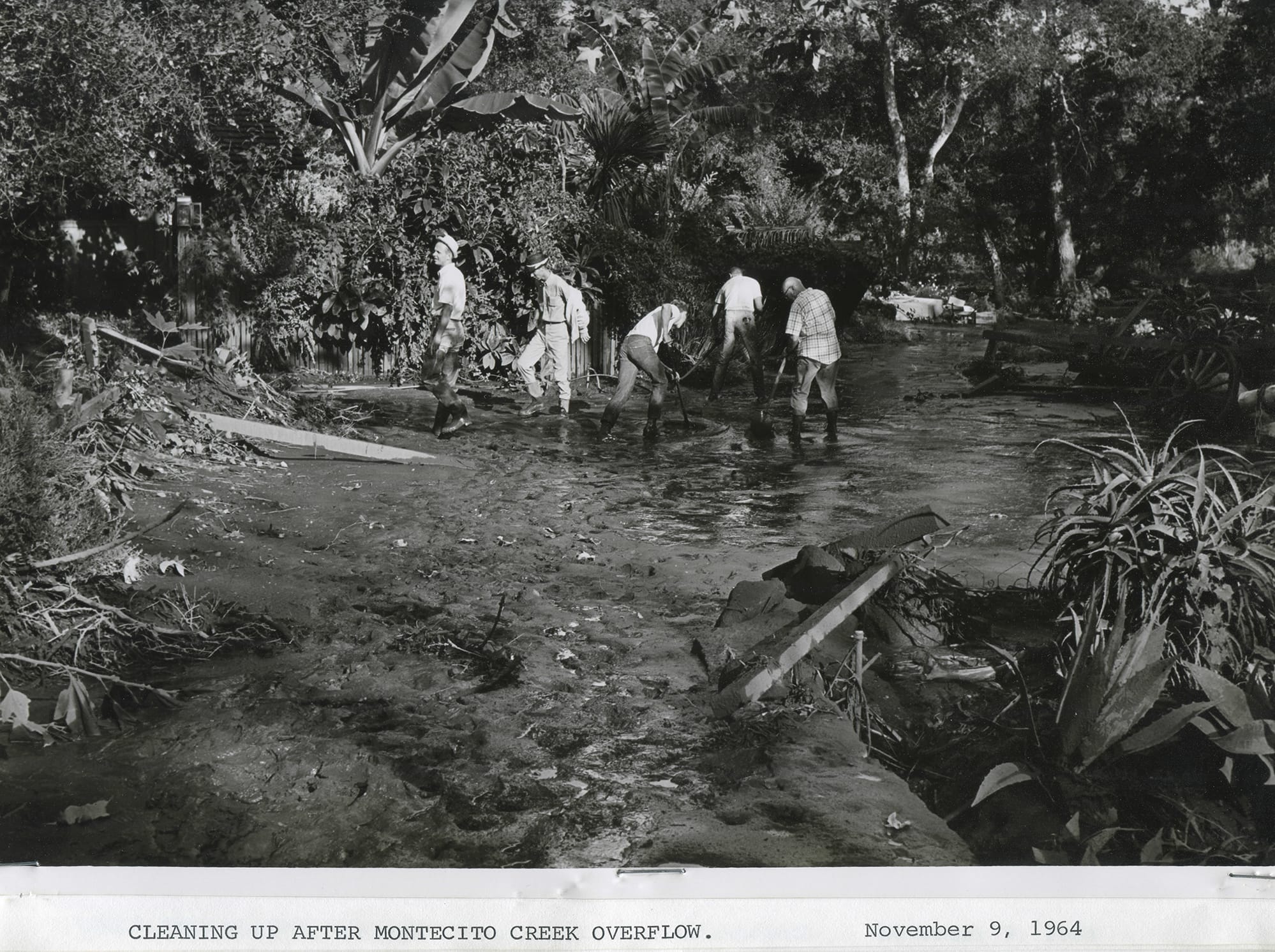

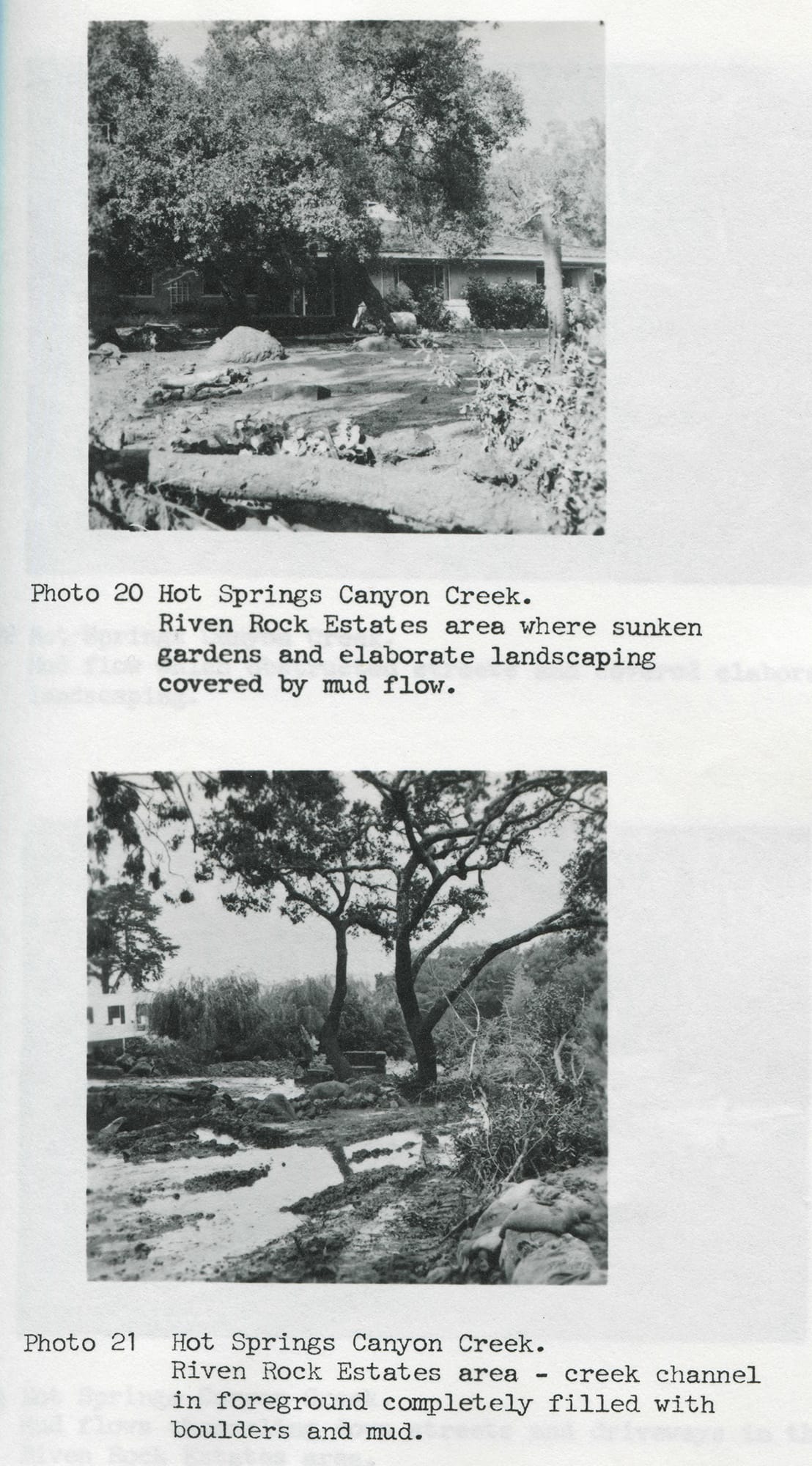

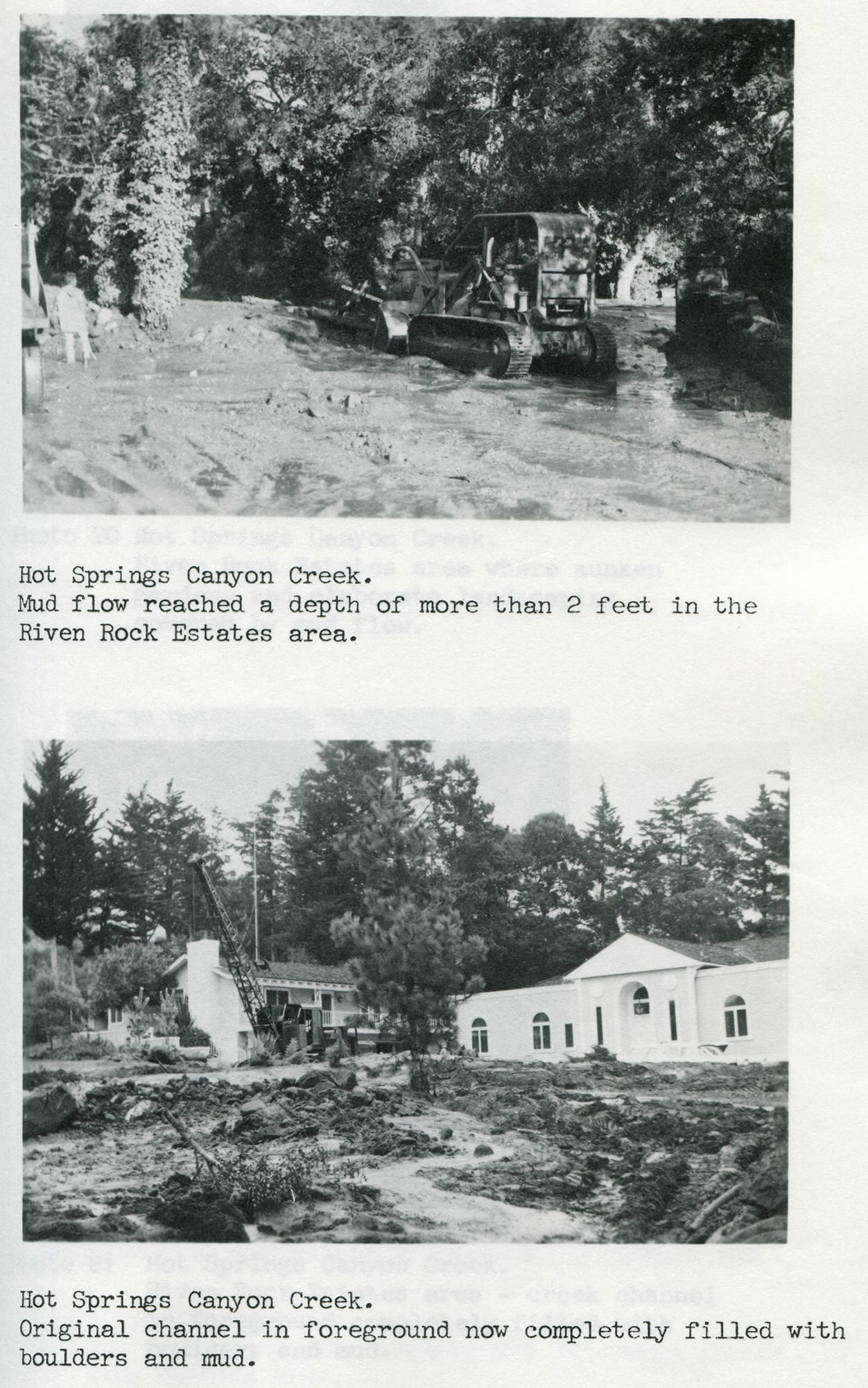

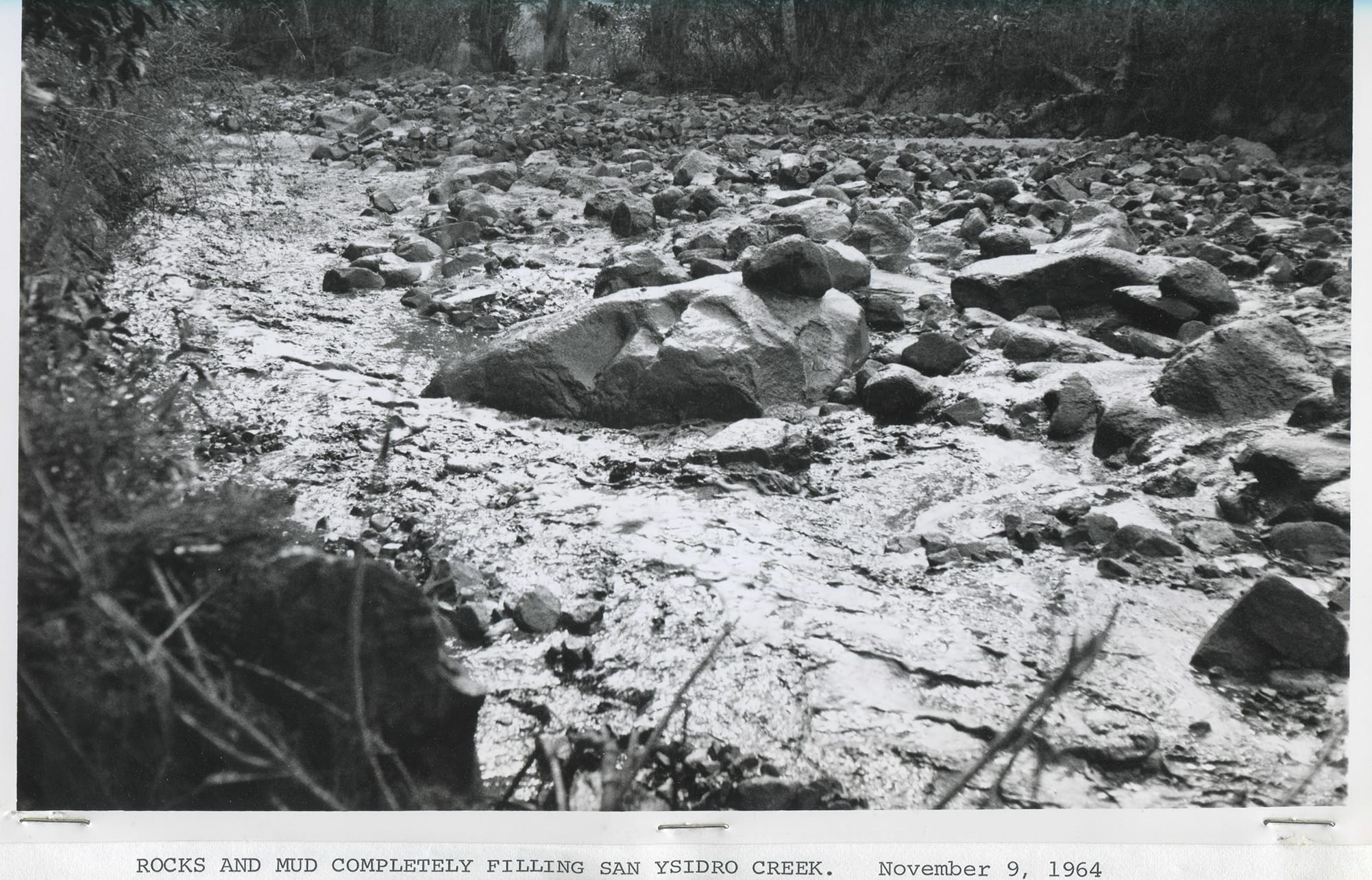

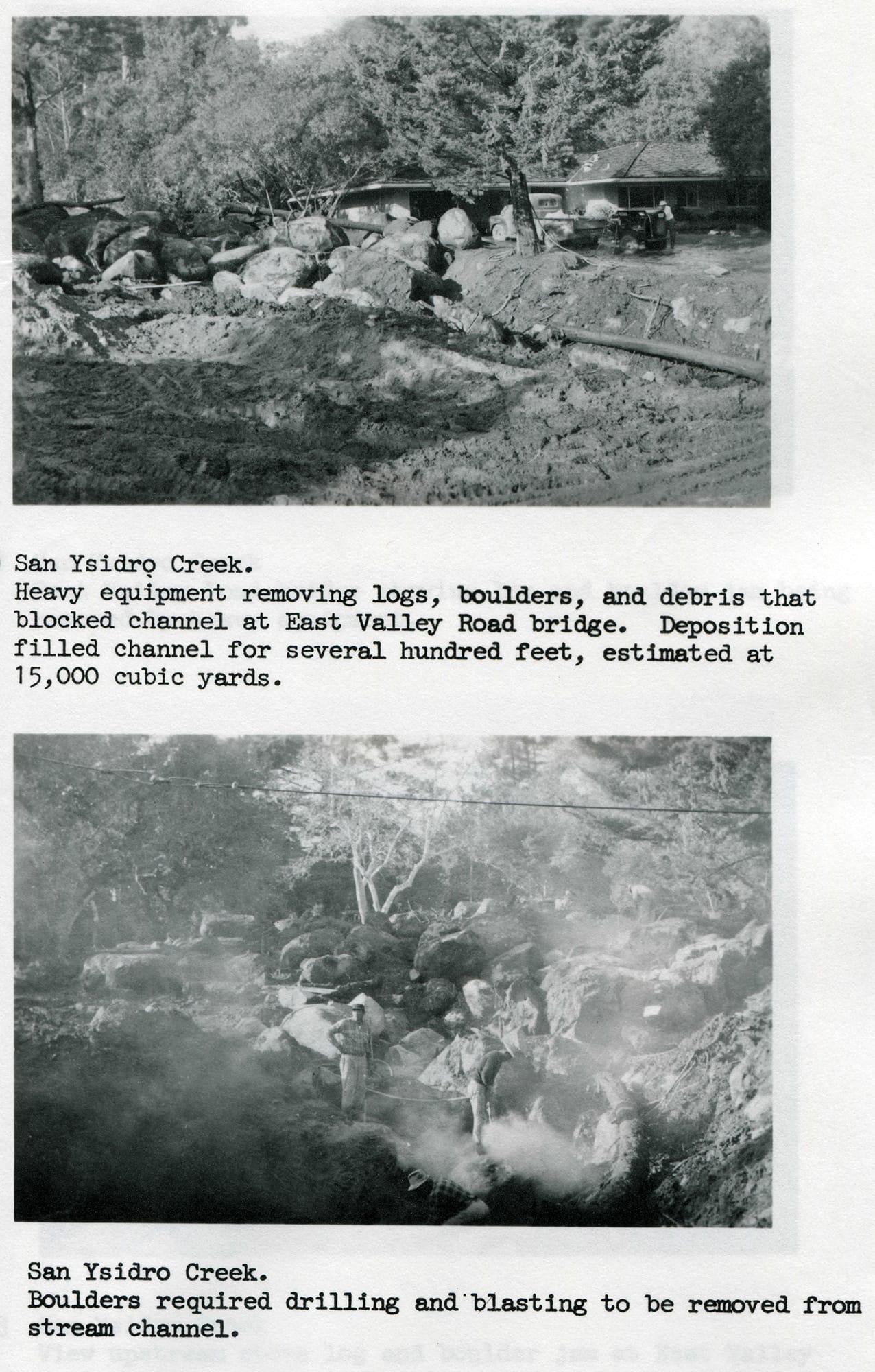

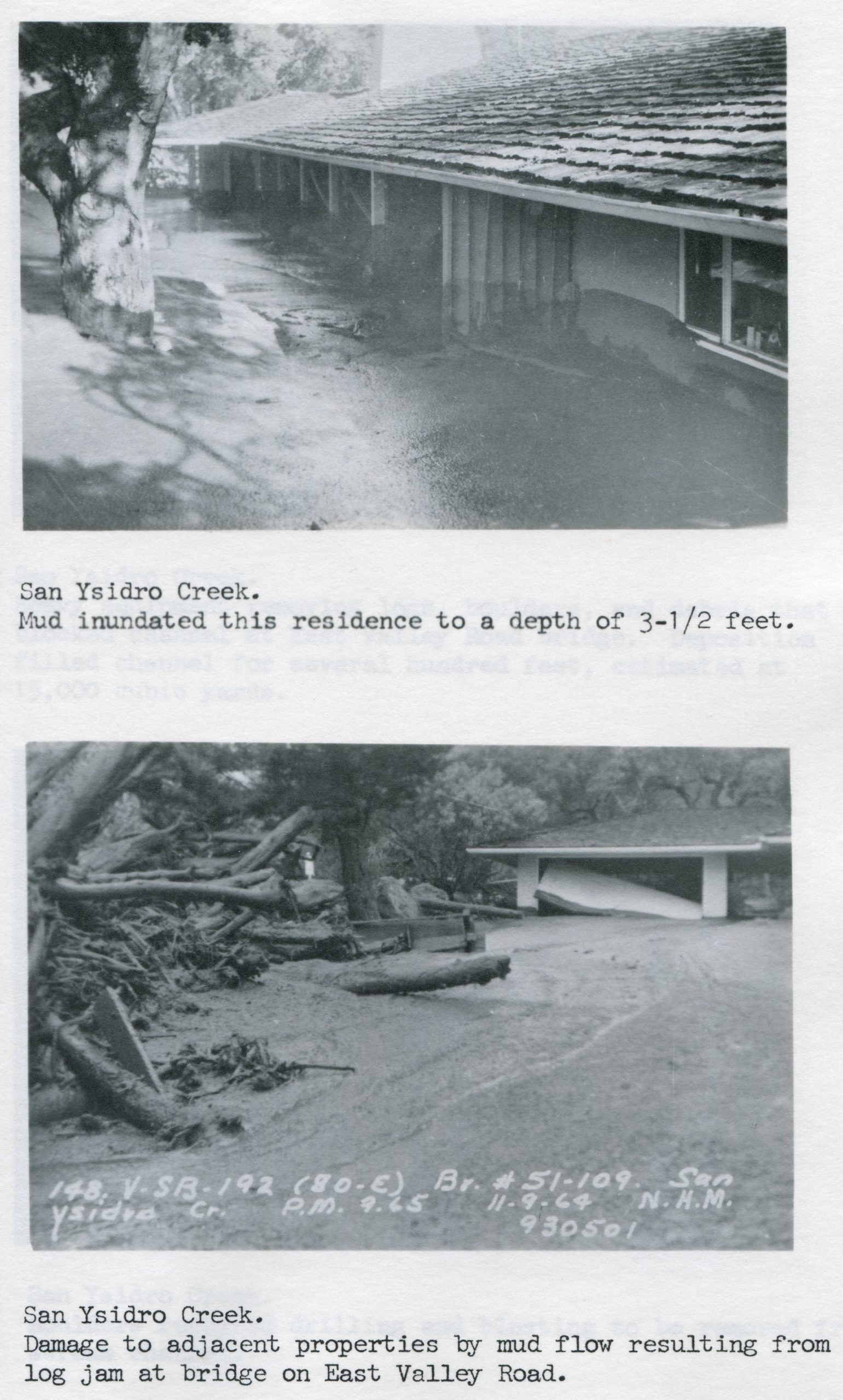

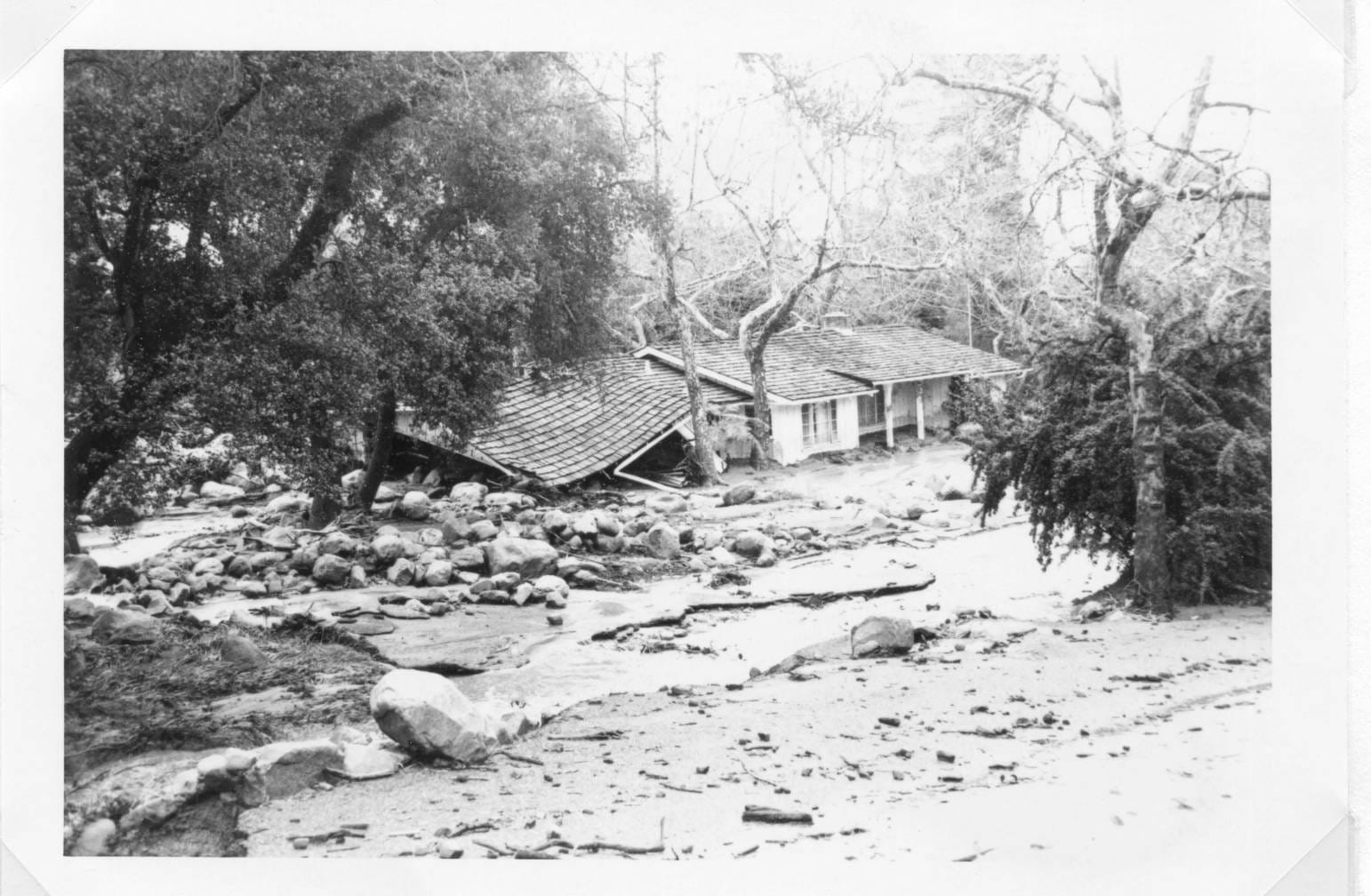

Just over a month later, on November 9, a rain burst of upward of 1.15 inches caused severe flooding of Cold Spring, Hot Springs, Montecito, and San Ysidro creeks. Eye witnesses in Cold Spring Canyon reported 20-foot walls of water, mud, rocks, and logs rushing at 15 miles per hour. Bridges that were not immediately swept away became clogged with logs and rocks, forcing backed-up water and debris to move laterally through nearby residential areas, causing severe damage. While devastating, some of the damaging effects of the flood were greatly mitigated by previous channel-clearing efforts conducted by the Army Corps of Engineers.

Montecito Creek become plugged under a bridge at Hot Springs Road, forcing the debris-latten water to flow down Hot Springs and Olive Mill roads. The flow continued down into the Lower Village, where it damaged commercial buildings and crossed the overpass to spill into streets on the south side of Highway 101.

Higher up, Hot Springs Creek backed up and diverted into the Riven Rock neighborhood, causing damage to landscaping and garages. San Ysidro Creek also backed up, pushing a deep mudflow onto East Valley Road.

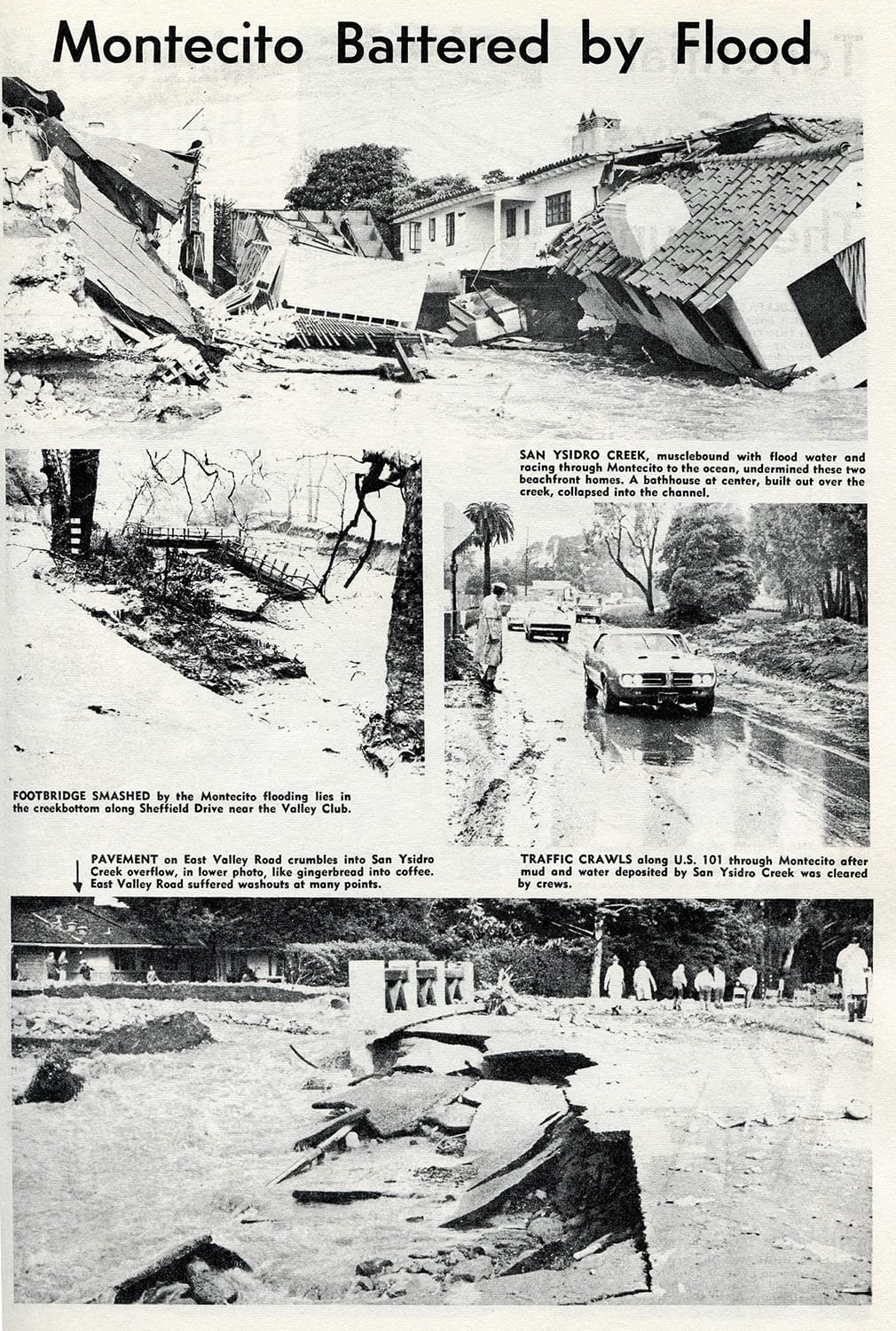

A major flood on January 25, 1969, came at the tail end of a week-long storm event, during which nearly nine inches of rain fell on Montecito. Luckily for some residents along Cold Spring Creek, a debris dam put in place after flooding in 1964 prevented substantial damages. Areas in the vicinity of Montecito, Buena Vista, San Ysidro, and Romero creeks were not so lucky. Montecito Creek crested its banks again — as it had done in 1914 and 1965 — to flow down Olive Mill Road to the Lower Village. San Ysidro Creek flooded the Glen Oaks neighborhood and caused substantial damage to beachfront properties near its outlet to the sea, at Posilipo Lane. Damage was also reported along Romero and Buena Vista creeks, and East Valley Road was covered in mud from Ortega Ridge Road to Sheffield Drive.

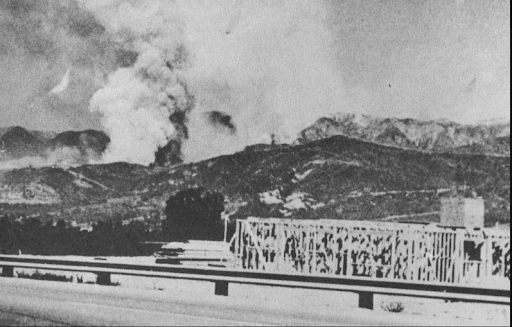

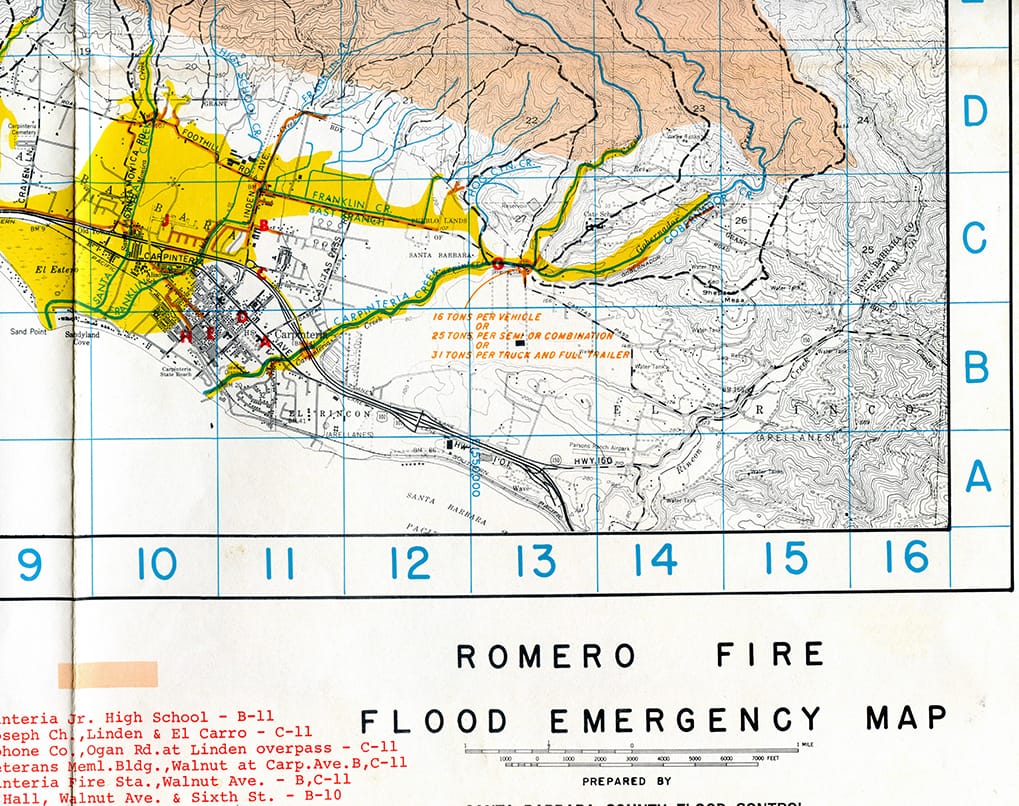

An act of arson, the Romero Fire was started on October 6, 1971, when a man threw an improvised fire bomb onto the steep dry slopes off Bella Vista Drive. The fire was reported about 30 minutes later when the smoke became visible in the hills behind Montecito and Summerland. The Forest Service responded, with the aid of Montecito and Carpinteria firefighters; however it was immediately apparent that the fire had already grown out of control. Aircraft and hand crews were dispatched to hold the fire at the East Camino Cielo fuel gap. However, as the sun set, Santa Ana winds push the fire down the mountainside and across Bella Vista Drive and Ladera Lane, destroying four houses. By the next morning the fire had burned all the way through Toro Canyon, threatening Carpinteria. With weather forecasts looking good, bulldozers are sent to cut a fire break through Santa Monica Canyon. Unfortunately, the weather predictions were incorrect, and another unexpected windstorm caused the fire to explode eastward toward the bulldozer crews. Many of the operators managed to escape the blaze, but four were killed when the fire trapped them on the ridgeline.

The next day, the fire continued eastward, and by Sunday it had reached Carpinteria High School. Luckily, a sea breeze managed to push the flames back up the hill before the fire could spread into downtown Carpinteria. For three days the fire continued eastward towards Ventura as an aggressive aerial assault continued. Eventually, firefighters managed to gain the upperhand and stop the fire at Rincon Creek, after it had burned 15,600 acres.

As the rainy season approached, the possibility of flooding loomed over the burn zone. In December, five days of steady rain caused moderate to severe flooding along Romero and Toro Canyon creeks. In Summerland, flooding shut down Highway 101 and the railroad for several hours.

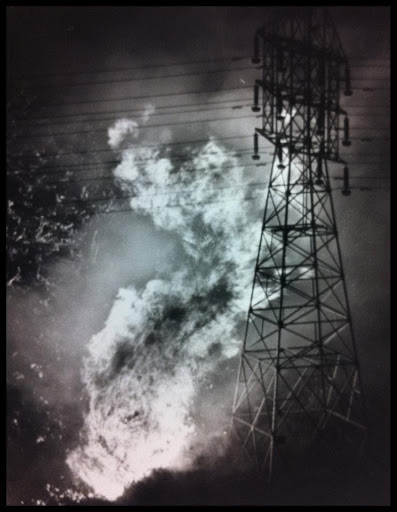

The Sycamore Fire began on July 26, 1977, in the midst of prolonged drought and high temperatures. The fire began at approximately 7:30 p.m. after a man lost control of a metal-framed kite that became entangled in power lines near Coyote Road and East Mountain Drive. The kite’s line caused an electric arc to shower the underlying brush with sparks. A call went out to Montecito Fire at around 7:40, and two trucks were immediately dispatched. At first the fire appeared to be manageable, and an air tanker was sent to drop retardant at around 8:20. However, at around 8:45, just after the airtanker had been grounded for the night, an extremely intense wind event caused the fire to explode out of control and quickly overwhelm firefighters.

With reported 90 mph gusts, the fire quickly spread, engulfing houses along Mountain Drive. Over the next few minutes the fire expanded rapidly in three directions — up into the foothills, down into Sycamore Canyon, and west into the Riviera community. Embers from burning roof shingles rained down in all directions. Soon, dozens of houses were ablaze. The situation grew worse as water pressure to fire hydrants failed due to mass numbers of people turning on their residential hoses and sprinklers in a desperate effort to save homes. Due to limited water and the sheer volume of burning structures, firefighters were forced to abandon all but the most easily accessible houses. Things finally turned around at 2:30 a.m. as a sea breeze pushed in a marine layer and sent the fire back up toward Mountain Drive, where firefighters managed to contain it. By sunrise the threat was over. In just seven hours, 234 structures had burned, totaling $26 million in damages.

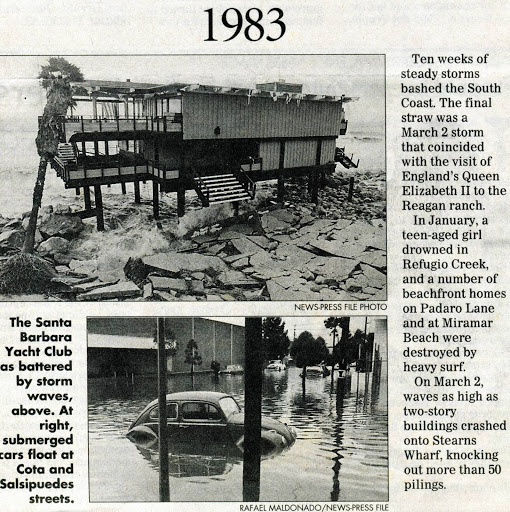

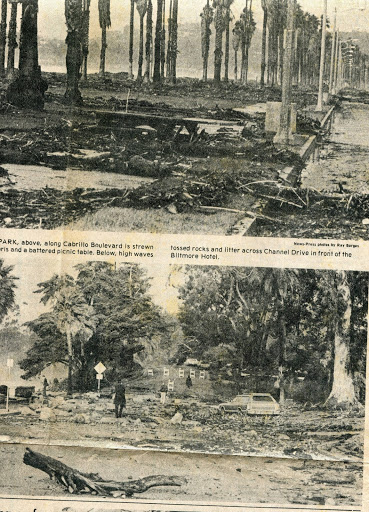

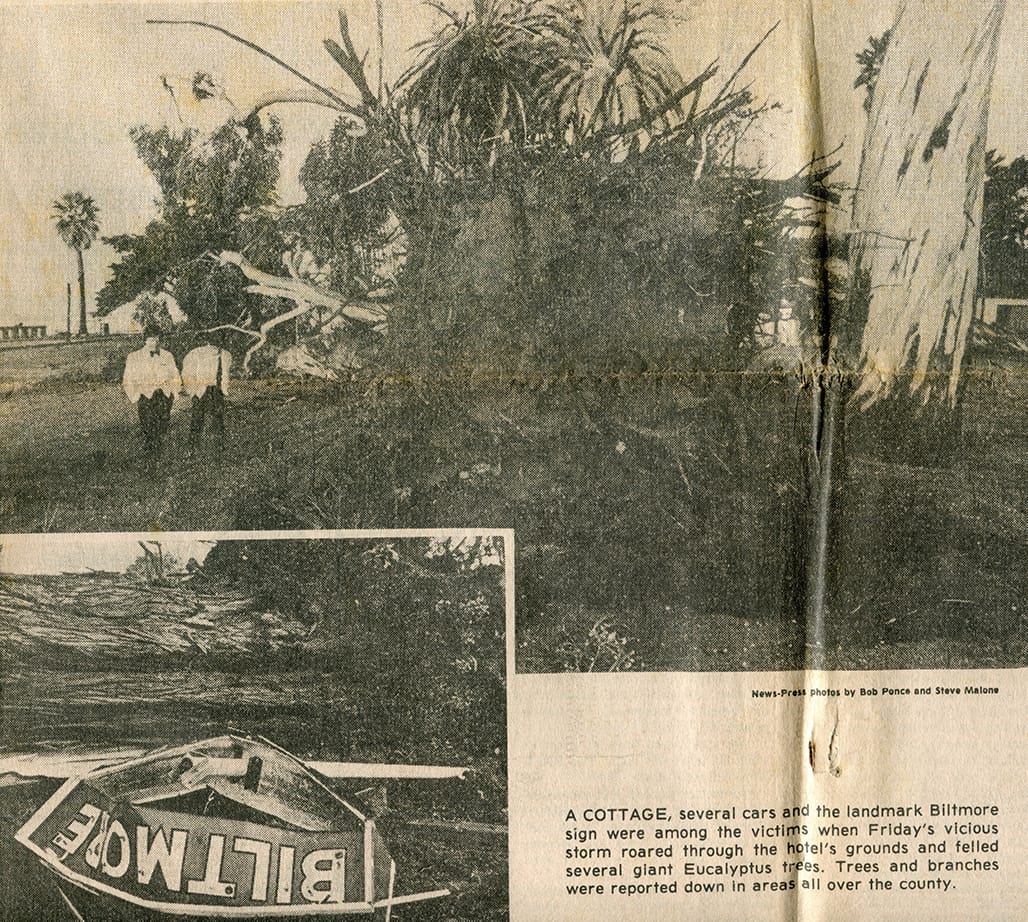

The winter of 1983 brought strong storms and unusually high surf to the Southern California coast. On the back of a record breaking El Niño, a series of storms lashed the coast, damaging numerous structures from Padaro Lane to Miramar Beach, as well as Stearns Wharf and Santa Barbara Harbor. Swollen Refugio Creek claimed the life of a teen-aged girl. On January 28, as a storm surge rode a full-moon high tide, waves in excess of seven feet crashed into houses along Edgecliff Lane and Miramar Beach, leaving about 40 homes badly damaged. Another 50 homes, from Santa Barbara to Ventura, also sustained damage.

The following night, another storm dropped nearly two inches of rain, accompanied by 51-mph winds recorded in Santa Barbara Harbor. By morning, the storm had knocked out power to more than 36,000 Edison customers and uprooted hundreds of trees countywide.

On March 2, waves topping 20 feet crashed into Stearns Wharf and took out more than 50 pilings. The nearby Santa Barbara Yacht Club was severely damaged and the harbor filled with wreckage and debris. Damages to the harbor alone were estimated at $1.5 million. Waves destroyed four homes and damaged dozens more on Padaro Lane. Seaside roads were flooded by stormsurf and excessive rainfall.

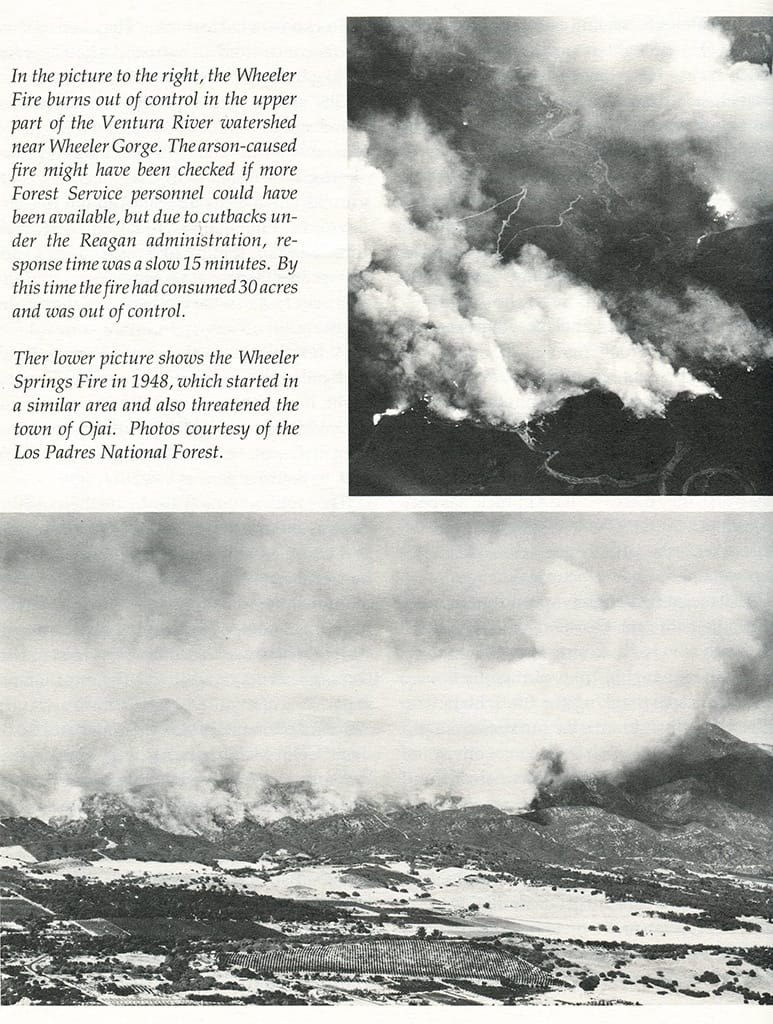

The Wheeler Fire broke out on July 1, 1985, when an arsonist ignited bushes in Wheeler Gorge, located about 15 miles northwest of Ojai. At the time it began, several other severe fires were burning throughout California and resources were stretched dangerously thin. Although the fire is reported immediately, logistical and communication issues delayed response, and by the time firefighters arrived, the fire had already spread wildly out of control.

For three days, down-canyon winds pushed the fire toward Ojai and into Matilija Canyon. As the fire approached Ojai, firefighters fought it house by house, and by the morning of July 4, the town had been saved, with no houses burned and only 11 structures damaged.

On the fire’s western front, strong winds were pushing the blaze through Matilija Canyon and up over the San Ynez Mountains. At 45,000 acres, the Wheeler Fire became the largest fire ever to be handled by a single team. As resources grew even more scarce due to logistical complications, the command structure all but collapsed before being reorganized on the evening of July 4. With the command structure restored, 125 engines were sent to protect Carpinteria. Luckily, favorable wind conditions pushed the fire back up the mountains and into the backcountry. The fire crept along the hills before it was finally contained on July 14. The Wheeler Fire burned 118,000 acres, 19 homes, 37 outbuildings, and destroyed or damaged $3 million in agricultural resources.

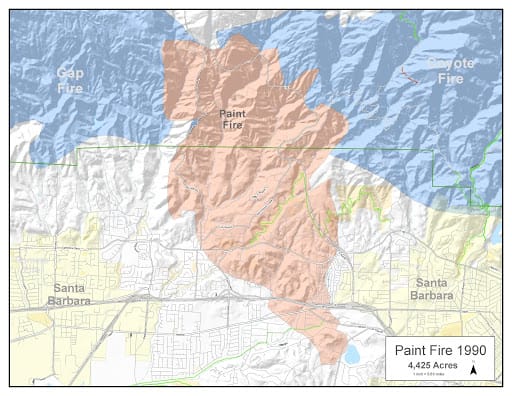

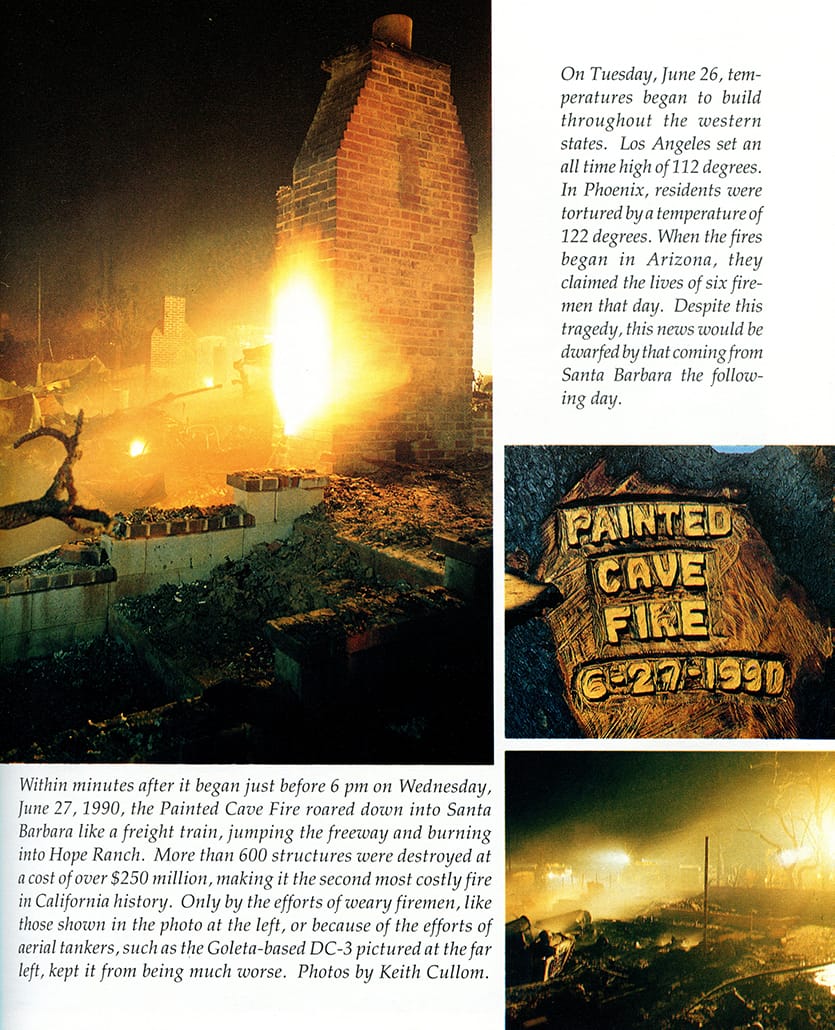

The Paint Fire — more commonly referred to as the Painted Cave Fire — began on June 27, 1990, and was the most intense and destructive fire to burn the Santa Barbara area in decades. The month of June had been unusually hot and dry. The temperature on the day of the fire reached 109 degrees, and gusting winds maxed out at 75 mph.

Stemming from a property dispute, the fire was started intentionally around 6 p.m. near Highway 154 and Painted Cave Road. Pushed by offshore winds coming down San Marcos Pass, the wildfire quickly destroyed everything in its path as residents escaped with little time to gather belongings. As the firestorm reached the bottom of Highway 154, firefighters and civilians watched in awe as it jumped all six lanes of Highway 101 and burned toward Hope Ranch.

Fortunately that night, the wind changed direction, coming off the ocean to push the fire back into its own burn scar, where there was no fuel remaining. Firefighters contained the blaze a few days later. The fire burned 5,000 acres and claimed 500 homes and buildings and one life.

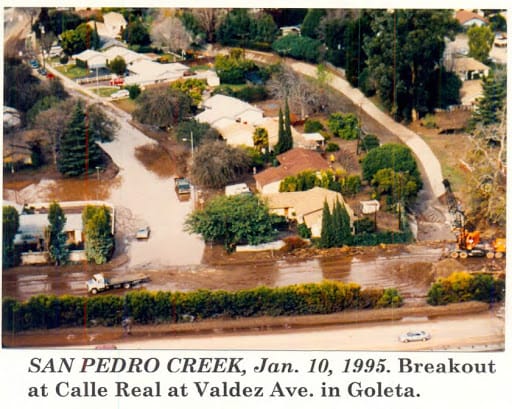

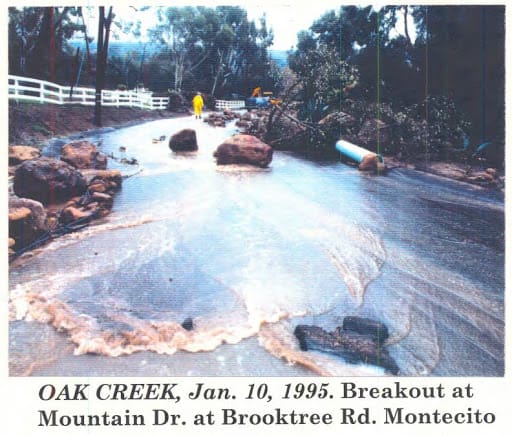

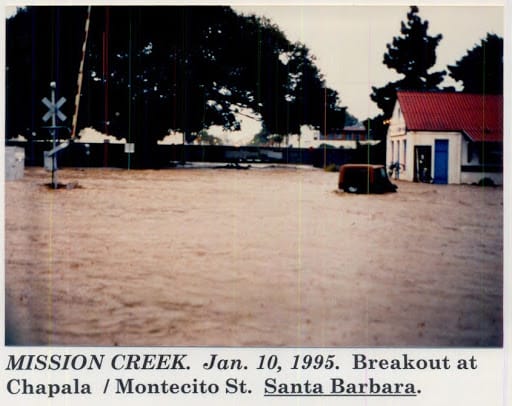

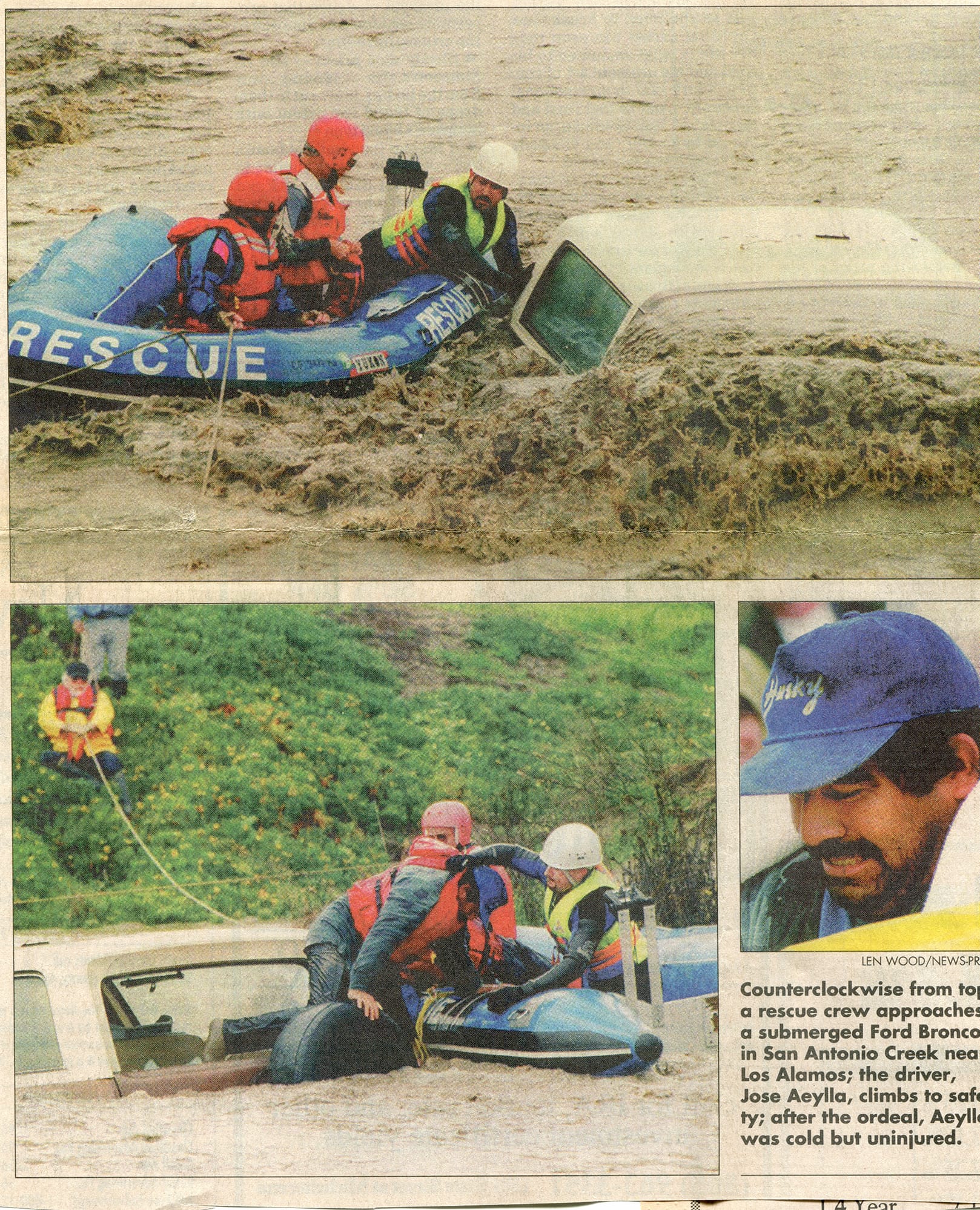

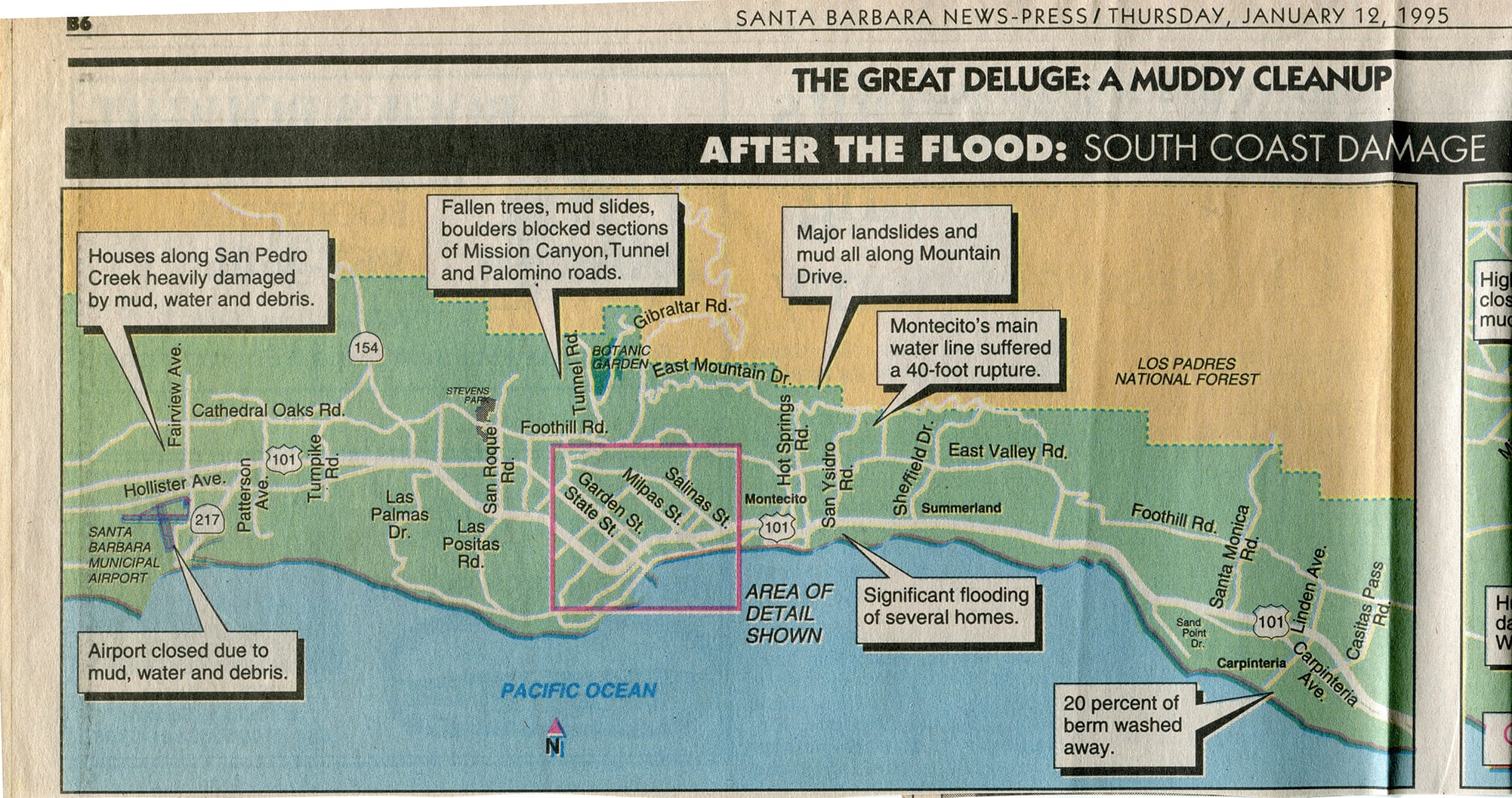

The winter of 1995 saw two major storm-related flooding events — first on January 10 , the second on March 10. Both caused significant flooding of creeks along the South Coast and shut down road and rail transportation for several hours.

The January 10 flood affected some 510 properties and caused roughly $50 million of damage. In Goleta, debris clogged culverts under Los Carneros Road and Highway 101, causing the Carneros and San Pedro creeks to overtop the highway and flow down Calle Real. Homes in the vicinity were flooded with up to three feet of mud and debris. San Jose Creek overflowed near Highway 217, causing severe severe flooding in downtown Goleta. Santa Barbara Airport, located in the Goleta Slough region near the convergence of all five of the area’s major creeks, was flooded for three days and out of service to all aircraft other than helicopters. Flood damage was mitigated along Atascadero Creek due to a channel clearing project that had been completed days prior to the storm’s arrival.

In Santa Barbara, Mission Creek gauges reported peak flows at 5,000 cubic feet per second, overtopping its banks at the De la Vina Street bridge near Alamar Avenue, causing flooding of the Cottage Hospital neighborhood. The creek also jumped its banks again at De la Guerra Street and flowed uncontrolled through the city to the ocean. Sycamore Creek flooded the five-way intersection at the top of North Salinas Street and, further downstream, the trailer parks near Highway 101.

Flooding in Montecito was less severe due to debris basins and channel clearing. However, on Mountain Drive, Bella Vista, and San Ysidro, plugged culverts caused creeks to divert down alternate routes for long distances before returning to their usual channels. These diversions caused serious roadway flooding and damage to residential structures. Montecito Creek also jumped is bank and flowed down Olive Mill Road, causing flooding in the neighborhood around Danielson Road and Virginia Lane.

The flooding event on March 10 played out in a similar fashion, with many of the same areas being hit. Some 300 structures were flooded causing about $30 million in damages. The airport was again flooded for days and San Jose Creek rushed at over 5,000 cubic feet per second, causing flooding in downtown Goleta. In Santa Barbara, the Mission Street underpass flooded, and a man drowned when he was swept away on Sycamore Canyon Road.

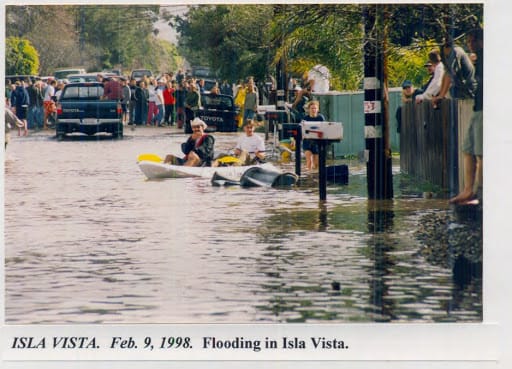

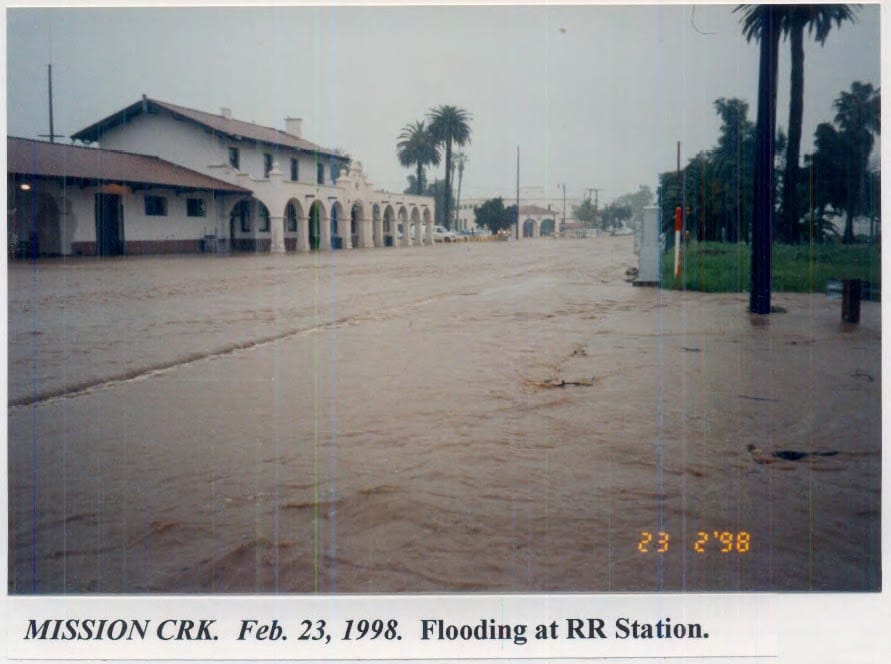

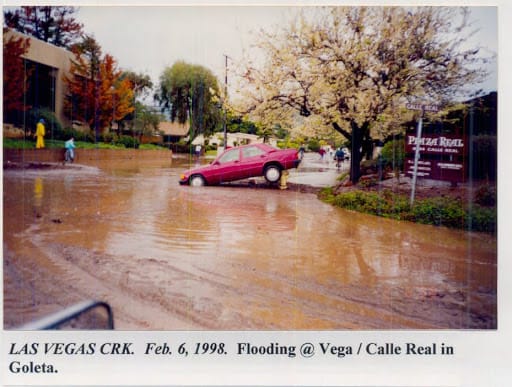

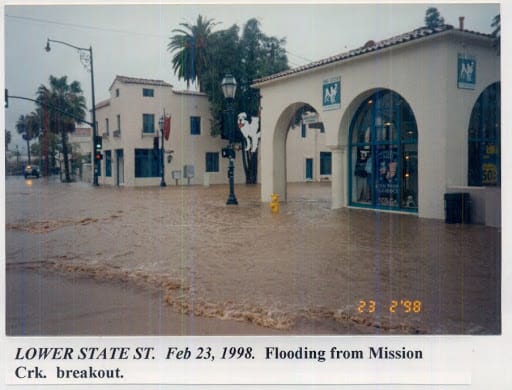

The flooding events of 1998 arrived on a strong El Niño and occurred throughout the month of February.

The first major incident occurred on February 2, when a storm bringing 63 mph winds took down hundreds of trees and powerlines, putting thousands of homes in the dark across Goleta and Santa Barbara. The next day, 15-foot-high waves damaged pilings under Stearns Wharf and a broken sewer line near Arroyo Burro Beach, closing several nearby beaches due to high levels of bacteria buildup. Flooding along a Gaviota creek caused damage to a Chevron facility, resulting in the accidental release of hazardous materials. The airport also closed down due to flood, and Highway 101 was shut down in Ventura.

On February 6, another storm brought intense rainfall to the Goleta area and overwhelmed Las Vegas, Encina, and San Pedro creeks. UCSB students were dismissed due to inundated classrooms and street flooding was widespread throughout Isla Vista and downtown Goleta. The airport was once again closed due to flooding, and major disruptions of transportation were widespread throughout the South Coast. In Santa Barbara, minor to moderate flooding occurred throughout town. Sycamore Canyon was evacuated, and one hiker drowned in Rattlesnake Canyon.

The El Niño’s final blow came on February 23-24 as heavy rain hit Montecito. All the major creeks overflowed and houses along San Leandro Lane, Veloz Drive, Santa Rosa Drive, and Olive Mill Road experienced flooding. While the events of 1998 were not as severe for the South Coast as the 1995 event, significant flooding and related damages occurred throughout the county, especially in the San Ynez, Lompoc, and Santa Maria valleys.

The Zaca fire began on July 4, 2007, deep in the Santa Ynez Mountains, when a rancher accidentally ignited dry brush with sparks from a metal grinder. Firefighters arrived quickly but the fire had already spread up the steep canyon into the difficult terrain of Zaca Ridge. Over the next few days the fire spread rapidly into Los Padres National Forest and the San Rafael Wilderness.

The wildfire was primarily driven by a heavy buildup of fuel that had not burned in many years. The dry and dense chaparral filling the region was so easily combustible that it often seemed to explode into flames upon contact with sparks or embers. These fuel-driven fires can move quickly and unpredictably with scorching hot temperatures, making ground fighting very dangerous. This and the fact that the region has little to no road access meant that firefighters were mostly restricted to aerial attacks. Luckily, the fire burned primarily in uninhabited wilderness, so containment strategy was focused on not letting it move south toward Santa Barbara and Ventura.

While the efforts to keep the fire in the backcountry were ultimately successful, the 240,000-acre fire took three months to contain at a cost of $118 million. No homes burned. Structure damages were limited to a single Forest Service outpost and a helicopter that crashed during takeoff from Figueroa Mountain.

Started on July 1 as an act of arson, the Gap Fire quickly became the most dangerous fire to hit the Santa Barbara front country since 1990’s Paint Fire. When firefighters arrived to West Camino Cielo Road, the blaze had spread less than a quarter of an acre and was nearly extinguished before a sudden wind gust caused the fire to spread rapidly toward Goleta. Nearly 200 personnel accompanied by helicopters and bulldozers were sent out to fight the flames and began evacuations of La Patera and Glen Annie canyons.

By day two, only a few hundred acres had burned, and the fire seemed to be diminishing until another sundowner event fueled 100-foot-high flames.

By day three, the blaze had spread to 2,000 acres and was becoming a substantial threat to much of Goleta. The fire burned through power lines in Glen Annie Canyon, causing loss of power to nearly 150,000 homes from Isla Vista to Montecito, and a state of emergency was declared. Mandatory evacuations were ordered from West Camino Cielo to Cathedral Oaks between Fairview and Patterson, and also for the Haney Tract, Kinevan Ranch, Hidden Valley, and San Marcos Trout Club.

By July 4, there were 800 firefighters with 20 airplanes battling a blaze now spanning 5,500 acres. Firefighters along North Fairview Avenue saved hundreds of houses. By that evening, the fire was burning on three fronts — northward toward Camino Cielo; and east and west toward Highway 154 and downtown Goleta, respectively.

Mandatory evacuations expanded to Farren Road to Highway 154 as 50 mph sundowners threatened 100 homes in the Painted Cave and Trout Club communities.

By the morning of July 5, nearly 8,300 acres had been burned as the number of assigned personnel grew to 2,500. Firefighters held the fire’s progress at West Camino Cielo and along its southern and eastern flanks in Goleta. More favorable weather conditions and brush-clearing helped shift the battle toward Gaviota, but this main fire front was now heading into more difficult terrain.

The fire burned in the hills until July 28, blackending nearly 10,000 acres but causing relatively little structural damage. Firefighters credited the agricultural barrier of green avocado orchards and irrigated soil surrounding Goleta with saving the town.

Short-lived but devastating, the Tea Fire began on the evening of November 13 in the dry hills of the eponymous Tea Gardens, part of a long-abandoned Montecito estate. The blaze started when strong sundowner winds reignited the smoldering remains of an illegal bonfire from the previous night.

The first flames were reported around 5:45 p.m., and Montecito firefighters responded to what they believed to be a small brush fire of one or two acres. Upon arrival, however, firefighters found the blaze rapidly expanding and out of control. Gusts in excess of 70 mph caused the fire to explode into the foothills, endangering home from Montecito to Mission Canyon.

The immediate objective for firefighters was to set an evacuation perimeter along the base of the foothills from Alameda Padre Serra to Camino Cielo as strong winds fueled the uncontrolled blaze. Support crews arrived from Los Angeles and Vandenberg Air Force Base, and from several agencies in between.

By the next morning, more than 1,500 acres had burned. Fortunately, expected sundowners — even stronger than the first night — failed to materialize. Four days later the fire was out, but it had burned nearly 2,000 acres and destroyed 210 homes.

“Breaking news and aftermath news clips about the Tea Fire, November 13, 2008.”

Video courtesy of KEYT, with permission.

“Post-Tea Fire cleanup and sandbagging ahead of threatening rainstorm.” Video courtesy of KEYT, with permission.

The Jesusita Fire began on May 5 and burned until May 18, blackening 8,733 acres. The fire destroyed 80 homes and 79 outbuildings and commercial properties and was called the worst disaster in 25 years by Santa Barbara County Sheriff Bill Brown.

The fire was started by accident when contractors working on an unpermitted clearing of the Jesusita Trail left hot equipment unattended in dry grass. Aided by 50 mph winds, the blaze quickly grew to 150 acres and a mandatory evacuation was issued for 1,200 homes north of Foothill Road, east of Morada Lane, and west of El Cielito and Gibraltar roads.

Heavy winds in the night caused the fire to grow rapidly and by the next morning the fire had exploded in two directions, burning 20 homes in San Roque Canyon to the west and bearing down on the Tea Fire burn scar to the east. Mandatory evacuations were expanded to include most of San Roque and Mission Canyon, as well as much of the Upper Riviera to State Street.

High winds continued that night and by morning of May 7, the wildfire had expanded to 3,500 acres. On the western flank, evacuations were again expanded to include the areas of De La Vina, Vernon, and Los Positas, as well as the area along Highway 101, Upper State Street and Highway 154. On the eastern flank, the areas of Milpas Street to San Ysidro Road and all the way up to Camino Cielo were evacuated as the fire pressed towards Montecito. In total, 30,000 residents were temporarily displaced.

More strong winds made things worse. The following morning, Chief Andrew DiMizio explained that “all hell broke loose” overnight as the blaze expanded in both directions in just a few hours. Total acreage burned had reached 8,700. Fortunately, staring on May 9, the situation began to improve as cool and humid weather came off the ocean and sundowners subsided. With nearly 4,000 firefighters, 12 airplanes, and 15 helicopters now gaining the upper hand, containment increased to 40%. The fire continued to burn into uninhabited backcountry, and the city of Santa Barbara was no longer in danger. The fire continued to smolder until it was finally extinguished on May 18. It caused an estimated $20 million in damages.

The Sherpa Fire started on the afternoon of June 15 at Rancho La Scherpa, near the top of Refugio Canyon along the Gaviota Coast. The fire began by accident when a ranch resident removed a burning log from a fireplace and placed it outside. Before he could extinguish it with a garden hose, wind pushed embers into nearby dry chaparral.

Mandatory evacuations were quickly ordered for Refugio, Venadito, and Las Flores canyons, as well as El Capitan State Park. Highway 101 was closed from Buellton to Winchester Canyon as fire crews aided by airplanes arrived. Sundowners blow strong all night and by the next morning the fire had spread to 1,100 acres. Over the next couple days nighttime winds continued to push the fire toward the coast. By 11 p.m. on June 17, the blaze had grown to 6,321 acres, and 1,230 active personnel continued to battle the flames.

The next morning, weather conditions changed favorably, and firefighters managed to increase containment. By June 22, the fire had burned 7,969 acres, with 89% containment. Full containment was reached on July 7. There were no fatalities and little structural damage.

Roughly six months later, on January 20, 2017, a powerful rainstorm struck the mountains along the Gaviota Coast. The heavy downpour quickly overwhelmed the creeks and other canyon drainages. Historic adobe dwellings in Las Flores Canyon were destroyed by flooding and debris. Nearby El Capitan Canyon Resort sustained severe damage and two dozen campers had to be rescued.

The Rey fire began around 3:15 pm on August 18th, 2016 when a dying tree fell on power lines near White Rock Campground. Within two day the fire had grown to over 10,000 acres, fueled by dense fuel buildup and erratic winds. Initially the firefighting effort proved difficult as the dense smoke plume made it difficult to determine the fire’s full size and area. Luckily, cool temperatures and nighttime marine layers allowed helicopters to more accurately judge the fire area and direction. These same weather conditions helped slow the fires growth at night and extensive fire lines along roads helped increase containment. By September 1st the fire was 96% contained and by September 16th it was extinguished. In total the blaze reached over 23,500 acres but damaged zero structures and claimed zero lives. In the aftermath, SoCal Edison and Frontier Communications were accused for being partially responsible for the fire in Court. SoCal had supposedly been aware of the danger posed by the dying tree and failed to take action. Frontier Communications also failed to conduct proper brush clearing underneath lines that went down.

The Whittier Fire began on July 7 when a hot vehicle ignited a tall patch of dry grass at Camp Whittier, located off Highway 154 near Lake Cachuma. The fire grew rapidly because of high temperatures and an abundance of fuel. The area had not burned in several decades.

Staff at the nearby Rancho Alegre were forced to evacuate without notice. Several of its structures were burned, and much of its livestock died. At the same time, around several dozen people, mostly children, were forced to shelter in place at Circle V Ranch Camp as the fire burned around them. The fire grew to 7,800 acres and mandatory evacuations were issued for Highway 154 and West Camino Cielo west of the Winchester Gun Club. The fire grew steadily over the next few days to 13,000 acres as limited vehicle access and a lack of natural barriers complicated containment efforts.

Despite difficult terrain, moderate winds and high humidity allowed firefighters to reach 52% containment by the end of the week. An unexpected wind event on the night of Friday the 13th caused the fire to expand in several directions. By the following morning the fire had grown to 17,000 acres and containment fell to 35%.

By July 16, 2,200 firefighters were assigned to the area and over 2,700 people were under evacuation. Over the next several days, aggressive aerial assaults and use of the Sherpa Fire burn scar allowed firefighters to slow the fire’s growth and gradually increase containment. Containment did reach 100% until October 5, and infrared scans still showed lingering hotspots for months to come. The Sherpa Fire burned 18,291 acres, destroying 16 structures.

Roughly 18 months later, on the morning of February 2, 2019, a strong downpour across the burn scar of the Whittier Fire trigger a debris flow in Duval Canyon. The event clogged and damaged a culvert beneath Highway 154, shutting down all lanes in both directions for a month.

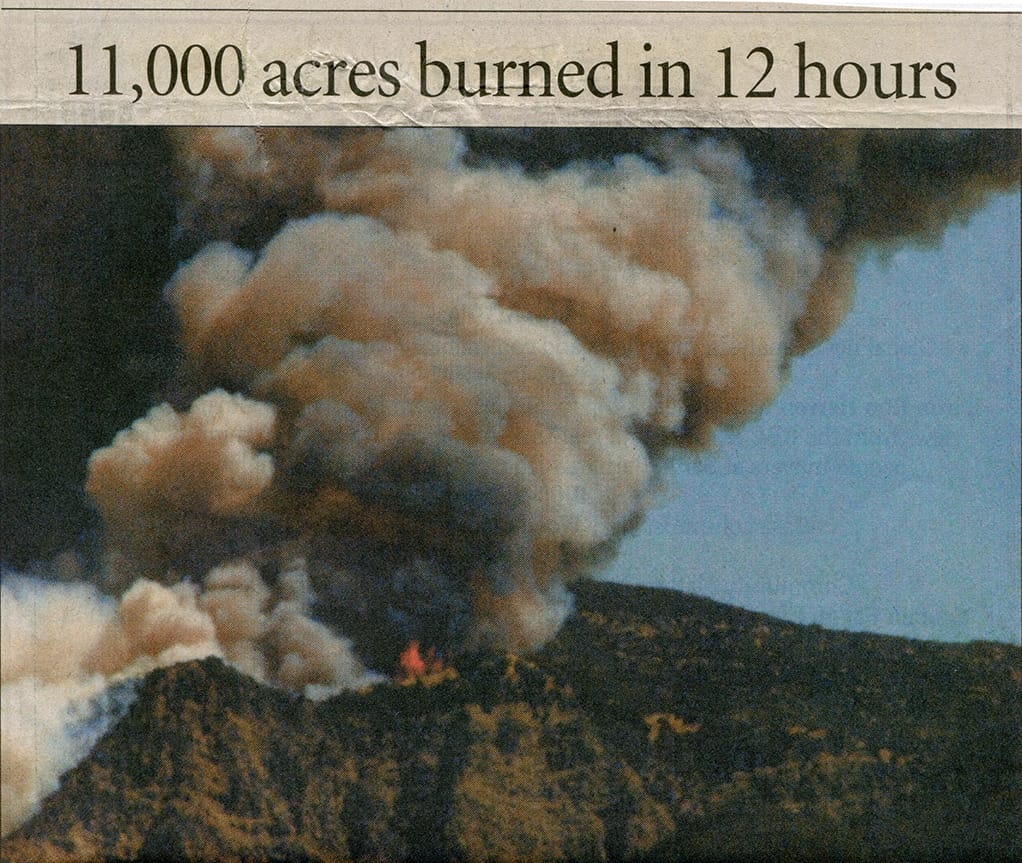

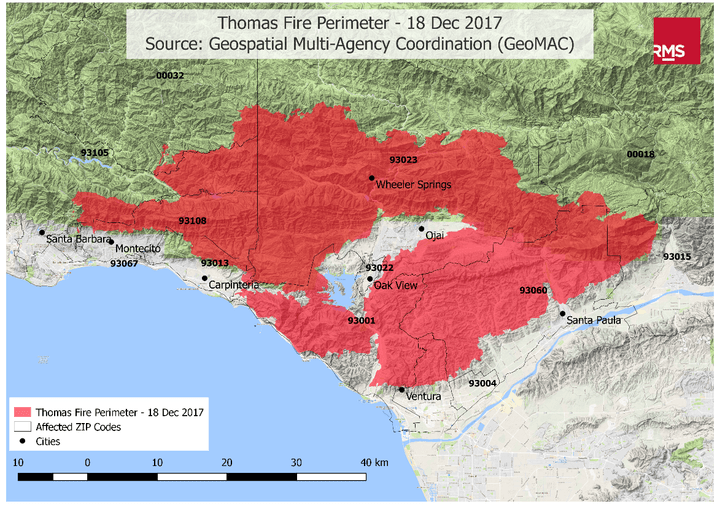

The Thomas Fire began on December 4 in Santa Paula, about 40 miles east of Santa Barbara. In the coming weeks, it became the largest fire in the history of California recordkeeping. The wildfire began when strong winds caused SoCal Edison power lines near Thomas Aquinas College to explode in an electrical arc, igniting dry grass below. Flued by strong winds, the fire grew to 500 acres within an hour and crossed Highway 150 into Santa Paula.

At around 10 p.m., the fire took out a SoCal Edison plant and knocked out power to some 100,000 homes and businesses, including most of the city of Ventura and up through Goleta. By 11 p.m. the fire had grown to 20,000 acres and was visible in the hills above Ventura City Hall. Thousands of residents evacuated. By daybreak, the fire had grown to 40,000 acres and 150 buildings in Ventura had been destroyed including Vista Del Mar hospital.

That morning, the fire’s western front jumped Highway 33 and began burning into Casitas Springs while its eastern front burned towards the town of Fillmore. The fire was now 50,000 acres and a mandatory 10 p.m. curfew was issued for the entire city of Ventura. A boil-water warning was also issued for the cities of Ventura and Ojai as the fire threatened pumps at Casitas Water District, and the town of La Conchita, along the edge of the Pacific Ocean, was evacuated.

By 9 a.m. on December 6, the fire had grown to 65,000 acres with zero containment and a hazardous air warning had been issued for the cities of Ventura, Oxnard, and Camarillo, as thick smoke was blown back at the coast by onshore winds. That evening, as the bulk of the blaze burned west from Ventura, the northern edge of the fire burned up and around the mountains surrounding the city of Ojai. The entire city was placed under a rapid mandatory evacuation.

That night, the fire’s southern edge moved closer to La Conchita and jumped Highway 101 at Seacliff Drive. Authorities closed the freeway in both directions. The fire continued to burn through the hills and by 6 p.m. on December 7, it had burned 115,000 acres and destroyed 439 structures. The next morning, ash was falling like snow from Ventura to Santa Barbara and people were told to stay inside and to wear dust masks outside. By then, 3,500 firefighters, 21 helicopters, 544 engines, 46 hand crews, and 26 bulldozers had been assigned to the now 132,000-acre fire that was only 10% contained. By December 9, the bulk of the blaze had moved on from Ventura and most of the city was taken off of mandatory evacuation. Some 530 structures had burned.

While Ventura was now mostly safe, the fire continued to grow rapidly and that night entered Santa Barbara County. At 1:40 a.m. on December 10, rolling blackouts began to hit Carpinteria and Santa Barbara. By 6 a.m. that morning mandatory evacuations were issued for large areas of Carpinteria, Summerland, and Montecito as the fire crept west along the mountainsides.

By noon, evacuation advisories were issued for much of eastern Santa Barbara as the blaze exploded into the foothills. By 6 p.m. the fire had grown to 230,000 acres and was so hot that it was creating its own weather patterns.

For the next two days the fire steadily crept north and west along the foothills as firefighters took advantage of onshore winds to perform a controlled backburn. By December 15, the fire had burned nearly 260,000 acres but containment was up to 40%, and its growth along the Santa Barbara foothills had been slowed by effective firefighting.

Just as people began to hope the blaze was reaching its conclusion, the Thomas fire roared back to life for a final show on the morning of December 16. Winds of up to 65 mph winds caused the fire to explode along the ridgeline. Evacuation were issued for all neighborhoods above Alameda Padre Serra and Salinas Street and the national guard was deployed to help maintain order.

As the fire’s westward expansion was halted the next day as it hit the Tea and Jesusita burn scars. From there, it continued to burn remote backcountry. By December 21, all evacuation orders in Santa Barbara County were lifted. The 272,000-acre fire was 65% contained. Over the next several days, containment grew significantly and by Christmas, firefighters had achieved 88%.

Full contained was reached on January 12, 2018. The Thomas Fire burned 281,000 acres, then the largest wildfire in state history. In total, 1063 structures were destroyed and two people lost their lives — one firefighter and a woman who died in a car accident fleeing the fire.

The 1/9 Debris Flow was triggered by a rare meteorological event following a high-intensity wildfire. The meteorological event, known as a Narrow Cold Frontal Rainband (NCFR), occurred when a narrow band of intense convection and rainfall built up along a cold front at around 1 a.m. on January 8, 2018. Moving east off the Pacific, the NCFR made initial landfall at Point Conception. As the storm progressed over land, the NCFR began to weaken and break apart, delivering heavy rains of over a dispersed area. However, as the mass of rain moved further eastward, it began to rapidly recondense, forming an atmospheric river directly over Santa Barbara and Montecito, dumping .66 inches of rain in 5 minutes.

Less than a month prior, the monstrous Thomas Fire had ravaged the mountains above Montecito, Summerland, and Carpentaria. The fire’s extremely high heat scorched the soil and caused the buildup of water-repellent ash that dramatically increased the rate of runoff carrying mud, burned trees, and large boulders down the mountain canyons.

A January 5 press conference focused on the substantial risk of high-intensity flooding. On January 7, mandatory and voluntary evacuations were issued for the Montecito foothills. The following day, law enforcement began door-to-door evacuation notifications. At approximately 3:30 a.m. on January 9, the brunt of the storm hit Montecito, Summerland, and Carpinteria, and causing millions of tons of water, rock, logs, and mud to come rushing down the mountain canyons.

Montecito was hit the hardest, its creeks becoming quickly overwhelmed and bridges clogged. The leading edges of several debris flows that rushed down a handful of major watersheds measured 30 feet deep in some areas. Entire neighborhoods were obliterated. About 100 homes were destroyed, and some 500 damaged. 23 residents died; two bodies, both children, remain unaccounted for. Many residents, some with traumatic injuries, were trapped on their roofs or within collapsed structures. Highway 101 at the Olive Mill Road overpass was flooded; both directions were shut down for two weeks.

Utilities were offline for several days, and major flooding and deposited mud and debris and downed power lines rendered many roads impassable. On January 11, Montecito was declared a Public Safety Evacuation Zone and remained off limits to the general public for two weeks as recovery crews worked to get services back online.

The 1/9 Debris Flow was the worst natural disaster in Santa Barbara County history.

Record-setting daytime temperatures spiked past 102 degrees during the evening of Friday, July 6, as strong sundowners blasted much of Santa Barbara’s coastal region. At approximately 8:40 p.m., emergency personnel received the first 9-1-1 call about a fast-moving wildfire in the Holiday Hill neighborhood, located north of Cathedral Oaks Road in Goleta. The first wave of firefighters arrived within four minutes after dispatch; the fire had already ignited nine homes.

Of the more than 3,000 nearby residents alerted, an estimated 2,500 evacuated. By midnight, the Holiday Fire had consumed more than 100 acres and 20 structures, including a dozen homes. Public safety leaders declared a local emergency around 1 a.m. on Saturday. Firefighters received a respite about an hour later as the winds settled down and temperatures slowly dropped. The fire was under control within about 12 hours of breaking out and most of the evacuated returned to their homes late Saturday and Sunday.

The hot winds and record temperatures — unofficially recorded as 106 on Holiday Hill — also damaged avocado crops at Las Varas Ranch, eight miles to the west, where the temperature hit 115.

On the windy Monday afternoon of November 25, the Cave Fire sparked to life in Los Padres National Forest near Painted Cave, close to the intersection of Highway 154 and East Camino Cielo. Pushed downslope by steady winds with gusts stronger than 50 mph, the fire quickly grew. Evacuation orders and warnings were sent out to thousands of nearby residents and a local emergency was declared. One outbuilding was burned on the first night. At its peak, the firefighting effort featured 600 personnel and ten air tankers. Within 24 hours, fortunately, the winds died down and temperatures cooled considerably. On the second night, a cold front brought rain to the region. The following night, before Thanksgiving, freezing temperatures visit the mountaintops, blanketing the burn scar with snow. The Cave Fire burned 3100 acres; its cause remains under investigation.

Sources:

- Geiger 1965:43; Engelhardt 1923:90-91; O’Keefe 1895:19; Writers’ Project 1941:188

- David F. Myrick. Vol. 1. Montecito and Santa Barbara: From Farms to Estates, 1988

- Walker A. Tompkins, Santa Barbara Yesterday, Montecito and Santa Barbara Vol. 1. Floods and Fires of the Early 1900s

- Maria Churchill, The Way We Were. Disasters of past years, Dec, 1997

- Army Corps of Engineers fire & flood assessment, 1964

- David F. Myrick. Vol. 1. Montecito and Santa Barbara: Fires and floods of recent decades; Judy Pearce, Montecito Journal, Montecito Scrapbook, Feb 4, 2001

- Hillary Houser, Santa Barbara News-Press stories from (Jan 28 & 29, March 2), Winter Weather: Lessons of resilience and forgetting from the savage storms of 1983

- Ray Ford and Keith Cullom, Santa Barbara Wildfires: Fire on the Hills, 1990.

- John Palminteri, Painted Cave Fire 25 Years Later – One Life and Nearly 500 Homes and Businesses Lost, KCOY, Jun 26, 2015

- 1995 Santa Barbara County flood report

- 1998 Santa Barbara County flood report

- Wildland Fire, Lessons learned Center: The Zaca Fire: Bridging Fire Science and Management;

- Sean Boyd, Zaca Fire Left its Mark on Santa Barbara County & the History Books, CAL OES News, Jul 11, 2017

- Marla Cone and Stuart Silverstien, Zaca fire burning way into state history, Los Angeles Times, Aug 20, 2007

- Ethan Stewart, The Great Gap fire of 2008, Santa Barbara Independent, Jul 10, 2008

- Chris Meagher, Terror on the Hill: The Brief but Violent Life of the Tea Fire, Santa Barbara Independent, Nov 20, 2008

- Noozhawk, live updates, May 6-14, 2009

- Oscar Flores, Whittier Fire is now 100 percent contained, 18,430 acres burned, KEYT, Oct 5, 2017

- Alex Johnson and Phil Helsel, California’s Whittier Fire Ravages Boy Scouts Camp, Kills Animals, NBC news, Jul 8, 2017

- Tom Bolton, Whittier Fire Puts on Menacing Show as Sundowner Winds Whip Flames, Noozhawk, Jul 14, 2017

- Veronica Rocha, Sherpa fire in Santa Barbara County started by hot embers from burning log, Los Angeles Times, May 3, 2017

- Joseph Serna, Heavy rain prevents Obama from landing in Palm Springs causes mudslides flooding across region, Los Angeles Times, Jan 20, 2017

- CountyofSB.org: Sherpa fire information and updates

- Chris O’neal, Thomas Fire | Timeline dec. 4 through dec. 13, Dec 13, 2017

- Joseph Serna and Melissa Etehad, Hundreds of homes in Montecito threatened as winds push Thomas fire toward coast: new evacuations, Los Angeles Times, Dec 16, 2017

- Joseph Serna, Southern California Edison power lines sparked deadly Thomas fire, investigators find, Los Angeles Times, Mar 13, 2019

- Nina Oakley and Marty Ralph, Meteorological Conditions Associated with the Deadly 9 January 2018 Debris Flow on the Thomas Fire Burn Area Impacting Montecito, January 16, 2018

- County of Santa Barbara Office of Emergency Management, Thomas Fire and 1/9 Debris Flow After-Action Report and Improvement Plan, October 16, 2018

- Santa Barbara Independent, November 25-27, 2019